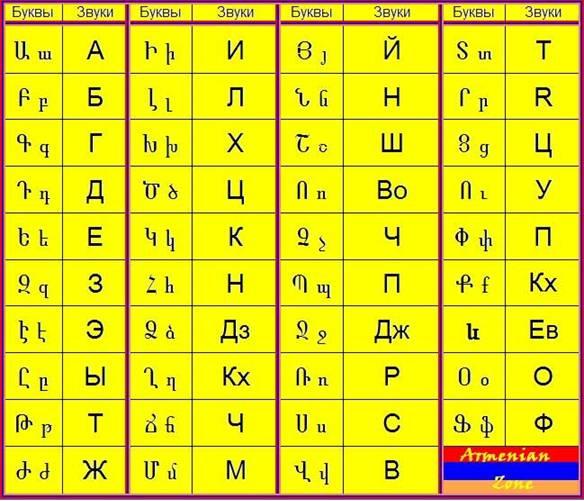

Armenian alphabet with English transcription. Alphabet. Creation of the alphabet: interesting facts

Armenian language ()- The Indo-European language is usually classified as a separate group, less often combined with Greek and Phrygian. Among the Indo-European languages, it is one of the oldest written languages. The Armenian alphabet was created by Mesrop Mashtots in 405-406. The total number of speakers around the world is about 6.7 million people. During its long history, the Armenian language has been in contact with many languages. Being a branch of the Indo-European language, Armenian subsequently came into contact with various Indo-European and non-Indo-European languages - both living and now dead, taking over from them and bringing to the present day much of what direct written evidence could not preserve. At different times, Hittite and hieroglyphic Luwian, Hurrian and Urartian, Akkadian, Aramaic and Syriac, Parthian and Persian, Georgian and Zan, Greek and Latin came into contact with the Armenian language. For the history of these languages and their speakers, data from the Armenian language are in many cases of paramount importance. This data is especially important for urartologists, Iranianists, and Kartvelists, who draw many facts about the history of the languages they study from Armenian.

Armenian is one of the Indo-European languages, forming a special group of this family. Number of speakers - 6.5 million. Distributed in Armenia (3 million people), USA and Russia (1 million each), France (250,000), Georgia, Iran, Syria (200,000 each), Turkey, Azerbaijan (150,000 each), Lebanon , Ukraine (100,000 each), Argentina (70,000), Uzbekistan (50,000) and other countries.

It belongs to the group of Indo-European languages, among which it is one of the ancient written ones. The history of the literary Armenian language is divided into 3 periods: ancient, middle and new. Ancient - from 5th to 11th centuries. The language of this period is called ancient Armenian, and the language of written monuments is called Grabar. The language of the middle period (11th-17th centuries) is called Middle Armenian. The new period (from the 17th century) is characterized by the formation of modern A. Ya., which already from the end of the 19th century. acquires the features of the New Armenian literary language. It is represented by eastern and western variants, divided into many dialects. The population of Armenia uses the eastern version - Ashkharabar.

The Armenian language began to be formed, in all likelihood, already in the 7th century. BC, and its Indo-European elements were layered on the language of the ancient population of Armenia, alien to it from time immemorial - the Urartians (Chaldians, Alarodians), preserved in the so-called Van cuneiform.

Most scientists (cf. Prof. P. Kretschmer, “Einleitung in die Geschichte d. Griechischen Sprache”, 1896) believe that this stratification was the result of an invasion of the foreign language region of Armenia by a people who were a group that broke away from the Thracian-Phrygian branch of the Indo -European languages.

The separation of the future “Armenian” group was caused by the invasion (in the second half of the 8th century BC) of the Cimmerians into the territory occupied by the Phrygian people. This theory is based on the news conveyed by Herodotus (Book VII, Chapter 73) that “the Armenians are a colony of the Phrygians.”

In the Baghistan inscription of Darius I, son of Hystaspes, both Armenians and Armenia are already mentioned as one of the regions that were part of the ancient Persian Achaemenid monarchy. The formation of the Armenian language took place through assimilation, to which the languages of the old population of the future Armenia were subjected.

In addition to the Urartians (Chaldians, Alarodians), the Armenians, during their consistent advance in the eastern and northeastern directions, undoubtedly assimilated into a number of other nationalities. This process occurred gradually over several centuries. Although Strabo (book XI, chapter 14) reports that in his time the peoples that were part of Armenia spoke the same language (“were monolingual”), one must think that in some places, especially on the peripheries, continued to survive native speech.

Thus, the Armenian language is a language of a mixed type, in which native non-Indo-European linguistic elements were combined with the facts of the Indo-European speech of the new colonizer-conquerors.

These non-Indo-European elements dominate mainly the vocabulary. They are comparatively less noticeable in grammar [see. L. Mseriants, “On the so-called “Van” (Urartian) lexical and suffixal elements in the Armenian language.”, M., 1902]. According to academician N. Ya. Marr, the non-Indo-European part of the Armenian language, revealed under the Indo-European layer, is related to the Japhetic languages (cf. Marr, “Japhetic elements in the language of Armenia”, Publishing House of Academy of Sciences, 1911, etc. work).

As a result of linguistic mixing, the Indo-European character of the Armenian language has undergone significant modifications both in grammar and vocabulary.

About the fate of the Armenian language until the 5th century. after the RH we have no evidence, with the exception of a few individual words (mainly proper names) that came down in the works of the ancient classics. Thus, we are deprived of the opportunity to trace the history of the development of the Armenian language over thousands of years (from the end of the 7th century BC to the beginning of the 5th century after the AD). The language of the wedge-shaped inscriptions of the kings of Urartu or the Kingdom of Van, which was replaced by Armenian statehood, genetically has nothing in common with the Armenian language.

We become familiar with ancient Armenian through written monuments dating back to the first half of the 5th century. after the Russian Empire, when Mesrop-Mashtots compiled a new alphabet for the Armenian language. This ancient Armenian literary language (the so-called “grabar”, that is, “written”) is already integral in grammatical and lexical terms, having as its basis one of the ancient Armenian dialects, which has risen to the level of literary speech. Perhaps this dialect was the dialect of the ancient Taron region, which played a very important role in the history of ancient Armenian culture (see L. Mseriants, “Studies on Armenian dialectology,” part I, M., 1897, pp. XII et seq.). We know almost nothing about other ancient Armenian dialects and only get acquainted with their descendants already in the New Armenian era.

Ancient Armenian literary language (" grabar") received its processing mainly thanks to the Armenian clergy. While the "grabar", having received a certain grammatical canon, was kept at a certain stage of its development, living, folk Armenian speech continued to develop freely. In a certain era, it enters a new phase of its evolution, which is usually called Central Armenian.

The Middle Armenian period is clearly visible in written monuments, starting only from the 12th century. Middle Armenian for the most part served as the organ of works intended for a wider range of readers (poetry, works of legal, medical and agricultural content).

In the Cilician period of Armenian history, due to the strengthening of urban life, the development of trade with the East and West, relations with European states, the Europeanization of the political system and life, folk speech became an organ of writing, almost equal to classical ancient Armenian.

A further step in the history of the evolution of the Armenian language. represents New Armenian, which developed from Middle Armenian. He received citizenship rights in literature only in the first half of the 19th century. There are two different New Armenian literary languages - one “Western” (Turkish Armenia and its colonies in Western Europe), the other “Eastern” (Armenia and its colonies in Russia, etc.). Middle and New Armenian differ significantly from Old Armenian both in grammatical and vocabulary terms. In morphology we have many new developments (for example, in the formation of the plural of names, forms of the passive voice, etc.), as well as a simplification of the formal composition in general. The syntax, in turn, has many peculiar features.

There are 6 vowels and 30 consonant phonemes in the Armenian language. A noun has 2 numbers. In some dialects, traces of the dual number remain. Grammatical gender has disappeared. There is a postpositive definite article. There are 7 cases and 8 types of declension. A verb has the categories of voice, aspect, person, number, mood, tense. Analytical constructions of verb forms are common. The morphology is predominantly agglutinative, with elements of analytism.

Armenian sound writing, created by an Armenian bishop Mesrop Mashtots

based on Greek (Byzantine) and Northern Aramaic script. Initially, the alphabet consisted of 36 letters, 7 of which conveyed vowels, and 29 letters represented consonants. Around the 12th century, two more were added: a vowel and a consonant.

Modern Armenian writing includes 39 letters. The graphics of the Armenian letter have historically undergone significant changes - from angular to more rounded and cursive forms.

There are good reasons to believe that its core, dating back to ancient Semitic writing, was used in Armenia long before Mashtots, but was banned with the adoption of Christianity. Mashtots was, apparently, only the initiator of its restoration, giving it state status and the author of the reform. The Armenian alphabet, along with Georgian and Korean, is considered by many researchers to be one of the most perfect.

Essay on the history of the Armenian language.

The place of the Armenian language among other Indo-European languages has been the subject of much debate; it has been suggested that Armenian may be a descendant of a language closely related to Phrygian (known from inscriptions found in ancient Anatolia).

The Armenian language belongs to the eastern (“Satem”) group of Indo-European languages and shows some similarities with the Baltic, Slavic and Indo-Iranian languages. However, given the geographical location of Armenia, it is not surprising that Armenian is also close to some Western (“centum”) Indo-European languages, primarily Greek.

The Armenian language is characterized by changes in the field of consonantism, which can be illustrated by the following examples: Latin dens, Greek o-don, Armenian a-tamn “tooth”; lat. genus, Greek genos, Armenian cin "birth". The advancement in Indo-European languages of stress on the penultimate syllable led to the disappearance of the stressed syllable in the Armenian language: Proto-Indo-European bheret turned into ebhret, which gave ebr in Armenian.

The Armenian ethnic group was formed in the 7th century. BC. on the Armenian Highlands.

In the history of the Armenian written and literary language, there are 3 stages: ancient (V-XI centuries), middle (XII-XVI centuries) and new (from the 17th century). The latter is represented by 2 variants: western (with the Constantinople dialect as the basis) and eastern (with the Ararat dialect as the basis).

The Eastern variant is the language of the indigenous population of the Republic of Armenia, located in the eastern region of historical Armenia, and part of the Armenian population of Iran. The eastern version of the literary language is multifunctional: it is the language of science, culture, all levels of education, the media, and there is a rich literature in it.

The Western version of the literary language is widespread among the Armenian population of the USA, France, Italy, Syria, Lebanon and other countries, immigrants from the western part of historical Armenia (the territory of modern Turkey). In the Western version of the Armenian language, there is literature of various genres, it is taught in Armenian educational institutions (Venice, Cyprus, Beirut, etc.), but it is limited in a number of areas of use, in particular in the field of natural and technical sciences, which are taught in the main languages of the corresponding regions.

The phonetics and grammar features of both variants are considered separately. As a result of centuries-old Persian domination, many Persian words entered the Armenian language. Christianity brought with it Greek and Syriac words. The Armenian lexicon also contains a large proportion of Turkish elements that penetrated during the long period when Armenia was part of the Ottoman Empire. There are also a few French words left, borrowed during the era of the Crusades.

The oldest written monuments in the Armenian language date back to the 5th century. One of the first is the translation of the Bible into the “classical” national language, which continued to exist as the language of the Armenian Church, and until the 19th century. was also the language of secular literature.

History of the development of the Armenian alphabet

The history of the creation of the Armenian alphabet is told to us, first of all, by one of Mashtots’ favorite students, Koryun, in his book “The Life of Mashtots” and Movses Khorenatsi in his “History of Armenia”. Other historians have used their information. From them we learn that Mashtots was from the village of Khatsekats in the Taron region, the son of a noble man named Vardan. As a child, he studied Greek literacy. Then, arriving at the court of Arshakuni, the kings of Great Armenia, he entered the service of the royal office and was the executor of the royal orders. The name Mashtots in its oldest form is referred to as Majdots. The famous historian G. Alishan derives it from the root "Mazd", which, in his opinion, "should have had a sacred meaning." The root "mazd", "majd" can be seen in the names Aramazd and Mazhan (Mazh(d)an, with the subsequent drop of the "d"). The last name is mentioned by Khorenatsi as the name of the high priest.

It seems to us that A. Martirosyan’s assumption is correct that “the name Mashtots apparently comes from the preferences of the priestly-pagan period of his family. It is known that after the adoption of Christianity by the Armenians, the sons of the priests were given into the service of the Christian church. The famous Albianid family (church dynasty in Armenia - S.B.) was of priestly origin. The Vardan clan could have been of the same origin, and the name Mashtots is a relic of the memory of this." It is undeniable that Mashtots came from a high class, as evidenced by his education and activities at the royal court.

Let us now listen to the testimony of Koryun: “He (Mashtots) became knowledgeable and skilled in worldly orders, and with his knowledge of military affairs he won the love of his warriors... And then,... renouncing worldly aspirations, he soon joined the ranks of hermits. After some time he and his students went to Gavar Gokhtn, where, with the assistance of the local prince, he again converted those who had departed from the true faith into the fold of Christianity, “rescuing everyone from the influence of the pagan traditions of their ancestors and the devilish worship of Satan, bringing them into submission to Christ.” This is how his main activity begins , so he entered church history as the second enlightener.To understand the motives of his educational activities, and then the motives for creating the alphabet, one must imagine the situation in which Armenia found itself at that period of its history, its external and internal atmosphere.

Armenia at that time was between two strong powers, the Eastern Roman Empire and Persia. In the 3rd century in Persia, the Arsacids were replaced by the Sassanid dynasty, which intended to carry out religious reform. Under King Shapukh I, Zoroastrianism became the state religion in Persia, which the Sassanids wanted to forcefully impose on Armenia. The answer was the adoption of Christianity by the Armenian king Trdat in 301. In this regard, A. Martirosyan accurately notes: “The conversion of Armenia to Christianity at the end of the 3rd and beginning of the 4th centuries was a response to the religious reform of Iran. In both Iran and Armenia they were introduced by special royal decrees, as an act of political will. In the first case, religion dictated aggression, in the second resistance."

In 387, Armenia was divided between Byzantium and Persia. The Armenian people did not want to put up with this situation. The Armenian Arsacid dynasty sought to restore the integrity of its kingdom. At that time, her only ally was the church, since the Naharars, being strong individually, waged internecine hostility. Thus, the church was the force that could, by becoming a mediator between the nakharars, raise the people.

At this time, the idea of nationalizing Christianity was born. After all, Christianity, which came to Armenia from Mesopotamia under Hellenistic conditions, was in an alien language and incomprehensible to the people. There was a need for national Christian literature in the native language so that it would be understandable to the people. If for a whole century after the adoption of Christianity the church did not need a national written language due to its cosmopolitan nature, then in the new conditions, after the division of the country, the role of the church changed. At this time, it sought to nationalize in order to become a consolidating core in society. It was at this time that the need for a national written language arose.

Thus, the political situation in Armenia forced Mashtots to leave his service at court and become a hermit. He commissioned works against Zoroastrianism from one of the prominent people of his time, Fyodor Momsuetsky. At the same time, he goes to the region of Gokhtn, located in close proximity to Persia and, therefore, more susceptible to its influence. In this regard, A. Martirosyan in his book comes to the following conclusion: “Mashtots leaves the court not out of disappointment, but with a very definite intention - to organize resistance against the growing Persian influence, the strengthening of Zoroastrianism in the part of divided Armenia that came under Persian rule” - and further concludes: “Thus, although Mashtots began his preaching work for the sake of spreading Christianity, however, with the clear intention of fighting against Zoroastrianism, Christianity had already taken root in Armenia and existed as a state religion for a whole century, so there seemed to be no special need to preach Christianity - if not for this question.

Christianity had to be given a special direction, to be aroused against Zoroastrianism, a doctrine whose bearer was the hostile Persian state. Religious teaching was turning into a weapon." Having ebullient energy, Mashtots saw that his efforts in preaching were not giving the result that he would like. An additional means of struggle was needed. This means should have been national literature. According to Koryun, after the mission to Goghtn Mashtots “conceived to take even more care of the consolation of the whole country, and therefore multiplied his continuous prayers, with open hands (raising) prayers to God, shed tears, remembering the words of the apostle, and said with concern: “Great is the sorrow and incessant torment of my heart for my brothers and relatives..."

So, besieged by sad worries, as if in a network of thoughts, he was in the abyss of thoughts about how to find a way out of his difficult situation. It was at this time, apparently, that Mashtots had the idea of creating an alphabet. He shares his thoughts with Patriarch Sahak the Great, who approved his thought and expressed his readiness to help in this matter.

It was decided to convene a council so that the highest clergy would approve the idea of creating a national alphabet. Koryun states: “For a long time they were engaged in inquiries and searches and endured many difficulties, then they announced the constant search for their Armenian king Vramshapuh.” The king, who had previously been outside the country, upon returning to Armenia, found Sahak the Great and Mashtots together with the bishops, concerned about finding the Armenian alphabet. Here the king told those gathered that while in Mesopotamia, he learned from the priest Abel a certain Syrian bishop Daniel, who had Armenian letters. This Daniel seemed to have unexpectedly found the forgotten old letters of the Armenian alphabet. Having heard this message, they asked the king to send a messenger to Daniel so that he would bring them these letters, which was done.

Having received the desired letters from the messenger, the king, together with Catholicos Sahak and Mashtots, were very happy. Youths from all places were gathered to learn new letters. After their training, the king ordered that the same letters be taught everywhere.

Koryun narrates: “For about two years, Mashtots was teaching and taught classes in these scripts. But... it turned out that these scripts were not sufficient to express all the sounds of the Armenian language.” After which these letters are discarded.

This is the history of the so-called Daniel letters, which, unfortunately, were not preserved in the chronicles and therefore cause a lot of misunderstandings among scientists. Firstly, the dispute is about the meaning of the phrase “suddenly found”. Were these really “forgotten Armenian letters” or did he confuse them with Aramaic (in the letter the words Armenian and Aramaic are written almost identically in Syriac). R. Acharyan believes that this could be an ancient Aramaic letter, which was no longer used in the 4th-5th centuries. These are all assumptions that do not clarify the picture. The very interesting hypothesis about S. Muravyov’s Danilov letters, which will be discussed later, did not clarify the picture either.

Let’s leave Daniel’s letters, to which we will return, and follow Mashtots’ further actions. Movses Khorenatsi narrates that “Following this, Mesrop himself personally goes to Mesopotamia, accompanied by his disciples to the mentioned Daniel, and, not finding anything more from him,” decides to independently deal with this problem. For this purpose, he, being in one of the cultural centers - in Edessa, visits the Edessa Library, where, apparently, there were ancient sources about writing, about their principles of construction (this idea seems convincing, since in principle, proposed for trial readers, the oldest view is seen in the writings). After searching for a certain time for the necessary principle and graphics, Mashtots finally achieves his goal and invents the alphabet of the Armenian language, and, adhering to the ancient secret principles of creating alphabets, he improved them. As a result, he created an original, perfect alphabet both from the point of view of graphics and from the point of view of phonetics, which is recognized by many famous scientists. Even time could not significantly affect him.

Mashtots describes the very act of creation of the Khorenatsi alphabet in his “History” as follows: “And (Mesrop) sees not a vision in a dream or a waking dream, but in his heart, with pre-spiritual eyes presenting to him the right hand writing on a stone, for the stone kept the markings, like footprints in the snow. And not only (this) appeared to him, but all the circumstances were collected in his mind, as in a certain vessel." Here is an amazing description of Mashtots' moment of insight (it is known that insight accompanies a creative discovery that occurs at the moment of the highest tension of the mind). It is similar to cases known in science. This description of a creative discovery that occurs at the moment of greatest tension of the mind through insight is similar to cases known in science, although many researchers have interpreted it as a direct divine suggestion to Mesrop. A striking example for comparison is the discovery of the periodic table of elements by Mendeleev in a dream. From this example, the meaning of the word “vessel” in Khorenatsi becomes clear - this is a system in which all the letters of the Mesropian alphabet are collected.

In this regard, it is necessary to emphasize one important idea: if Mashtots made a discovery (and there is no doubt about this) and the entire table with letters appeared before him, then, as in the case of the periodic table, there must be a principle connecting all the letter signs into a logical system. After all, a set of incoherent signs, firstly, is impossible to open, and, secondly, does not require a long search.

And further. This principle, no matter how individual and subjective it may be, must correspond to the principles of constructing ancient alphabets and, therefore, reflect the objective evolution of writing in general and alphabets in particular. This is precisely what some researchers did not take into account when they argued that Mashtots’s main merit was that he revealed all the sounds of the Armenian language, but graphics and signs have no meaning. A. Martirosyan even cites a case when the Dutch scientist Grott asked one nine-year-old girl to come up with a new letter, which she completed in three minutes. It is clear that in this case there was a set of random signs. Most people can complete this task in less time. If from the point of view of philology this statement is true, then from the point of view of the history of written culture it is wrong.

So, Mashtots, according to Koryun, created the Armenian alphabet in Edessa, arranging and giving names to the letters. Upon completion of his main mission in Edessa, he went to another Syrian city of Samosat, where he had previously sent some of his students to master the Greek sciences. Koryun reports the following about Mashtots’ stay in Samosat: “Then... he went to the city of Samosat, where he was received with honors by the bishop of the city and the church. There, in that same city, he found a certain calligrapher of Greek writing named Ropanos, with the help of whom designed and finally outlined all the differences in letters (letters) - thin and bold, short and long, separate and double - and began translations together with two men, his disciples... They began translating the Bible with the parable of Solomon, where at the very beginning he (Solomon) offers to know wisdom."

From this story, the purpose of visiting Samosat becomes clear - the newly created letters had to be given a beautiful appearance according to all the rules of calligraphy. From the same story we know that the first sentence written in the newly created alphabet was the opening sentence of the book of proverbs: “Know wisdom and instruction, understand sayings.” Having finished his business in Samosat, Mashtots and his students set off on the return journey.

At home he was greeted with great joy and enthusiasm. According to Koryun, when the news of the return of Mashtots with new writings reached the king and the Catholicos, they, accompanied by many noble nakharars, set out from the city and met the blessed one on the banks of the Rakh River (Araks - S.B.). "In the capital - Vagharshapat this joyful the event was solemnly celebrated.

Immediately after returning to his homeland, Mashtots began vigorous activity. Schools were founded with teaching in the Armenian language, where young men from various regions of Armenia were accepted. Mashtots and Sahak the Great began translation work, which required enormous effort, given that they were translating fundamental books of theology and philosophy.

At the same time, Mashtots continued his preaching activities in various regions of the country. Thus, with enormous energy, he continued his activities in three directions for the rest of his life.

This is the brief history of the creation of the Armenian alphabet.

original letter created by Mesrop Mashtots around 406. The emergence of the Armenian letter is associated with the spread of Christianity, adopted by the Armenians in 301, and the need to create liturgical literature in the Armenian language. The Armenian letter is phonetic in nature. Initially, the alphabet contained 36 simple characters, each of which corresponded to a specific phoneme. The combination of signs, like diacritics, is not typical for the Armenian letter. The exceptions are the signs ու (from ո + ու) for the vowel [u] and և (from ե + ւ), pronounced as . Both signs were absent in the alphabet of Mesrop Mashtots. Approximately after the 12th century. Two more graphemes are introduced into the alphabet: the sign օ [o] for the diphthong աւ and the sign ֆ for [f]. The latter was introduced due to the appearance of many borrowings containing the phoneme [f]. With these changes, the writings of Mesrop Mashtots are also used for the modern Armenian language. The letters of the Armenian script (before the transition to Arabic numerals) also had digital meanings: they served to designate numbers from 1 to 9999.

The question of the sources and nature of the prototypes of the Armenian letter has not received an unambiguous solution. The general principles of the construction of the alphabet of Mesrop Mashtots (the direction of writing from left to right, the presence of signs to indicate vowels, the separate writing of letters, their use in the meaning of numbers) indicate the probable influence of Greek phonetic writing. It is assumed that Mesrop Mashtots could partially use the so-called Daniel letters (22 characters), attributed to the Syrian bishop Daniel; It is possible to use one of the variants of Aramaic writing, as well as Pahlavi italics.

The form of the characters of the Armenian alphabet has undergone various changes over time. From 5th to 8th centuries. the so-called uncial letter (erkatagir) was used, which had several varieties. After the 12th century Round writing (boloragyr) was established, and later cursive and cursive writing. The Georgian letter (khutsuri) and the alphabet of the Caucasian Albanians show certain similarities with the Armenian script.

| Order- forged number |

Armenian letter |

Name | Digital meaning |

Trance- lite- walkie-talkie |

Order- forged number |

Armenian letter |

Name | Digital meaning |

Trance- lite- walkie-talkie |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ա ա | ayb | 1 | a | 19 | Ճ ճ | čē | 100 | č | |

| 2 | Բ բ | ben | 2 | b | 20 | Մ մ | men | 200 | m | |

| 3 | Գ գ | gim | 3 | g | 21 | Յ յ | yi | 300 | y | |

| 4 | Դ դ | da | 4 | d | 22 | Ն ն | nu | 400 | n | |

| 5 | Ե ե | eč̣ | 5 | e | 23 | Շ շ | ša | 500 | š | |

| 6 | Զ զ | za | 6 | z | 24 | Ո ո | o | 600 | o | |

| 7 | Է է | ē | 7 | ē | 25 | Չ չ | č̣a | 700 | č̣ | |

| 8 | Ը ը | ətʻ | 8 | ə | 26 | Պ պ | pē | 800 | p | |

| 9 | Թ թ | tʻo | 9 | tʻ | 27 | Ջ ջ | ǰē | 900 | ǰ | |

| 10 | Ժ ժ | žē | 10 | ž | 28 | Ռ ռ | ṙa | 1000 | ṙ | |

| 11 | Ի ի | ini | 20 | i | 29 | Ս ս | sē | 2000 | s | |

| 12 | Լ լ | livn | 30 | l | 30 | Վ վ | vew | 3000 | v | |

| 13 | Խ խ | xē | 40 | x | 31 | Տ տ | Tiwn | 4000 | t | |

| 14 | Ծ ծ | ca | 50 | c | 32 | Ր ր | rē | 5000 | r | |

| 15 | Կ կ | ken | 60 | k | 33 | Ց ց | co | 6000 | c̣ | |

| 16 | Հ հ | ho | 70 | h | 34 | Ւ ւ | hiwn | 7000 | w | |

| 17 | Ձ ձ | ja | 80 | j | 35 | Փ փ | pʻiwr | 8000 | pʻ | |

| 18 | Ղ ղ | łat | 90 | ł | 36 | Ք ք | kʻē | 9000 | kʻ | |

| 37 | Օ օ | o | o | |||||||

| 38 | Ֆ ֆ | fē | f | |||||||

| * The last two letters are a later addition and were absent from the Mesropian alphabet. | ||||||||||

Hypothetically the original source forms of the Armenian alphabet (5th century)

(based on reconstruction by S. N. Muravyov).

- Acharyan R., Armenian letters, Yerevan, 1968 (in Armenian);

- Abrahamyan A. G., History of Armenian writing and writing, Yerevan, 1959 (in Armenian);

- Koryun, Life of Mashtots, Er., 1962;

- Mesrop Mashtots. Collection of articles, Yerevan, 1962 (in Armenian);

- Sevak G. G., Mesrop Mashtots. Creation of Armenian letters and literature, Yerevan, 1962;

- Perikhanyan A. G., On the question of the origin of Armenian writing, in the book: Near Asian collection. Decipherment and interpretation of writings of the Ancient East, part 2, M., 1966;

- Tumanyan E. G., Once again about Mesrop Mashtots - the creator of the Armenian alphabet, “Izv. Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Ser. LiYa", 1968, vol. 27. century. 5;

- see also the literature under the article Armenian language.

About which I wrote earlier, Armenians have another symbol that they revere and treat with respect - the native Armenian alphabet. Traveling around Armenia you cannot help but notice this. Even a souvenir with letters is not just “tourist spoons” made in China, but much more.

Armenia has a peculiar cult of the letters of its alphabet. They are portrayed by artists, skilled craftsmen and children. All Armenian children not only know what the creator of the Armenian alphabet Mesrop Mashtots looks like, but they also draw him and can draw him. It's hard to imagine this in any other country.

Here is the most famous image of Mashtots, in the form of a man writing, to whom God himself dictates the alphabet (there is also such a version of his creation).

Monuments are erected to the letters. The main one is in Oshakan, a town near Yerevan. Here, in the church of St. Mesrop Mashtots (he is canonized by the AAC), the enlightener, is buried. In the courtyard of the church there are khachkars (slabs with filigree stone carvings) with letters inscribed on them.

In the photo you can see the capital letter Տ (No. 31), and in the distance – Կ (No. 15).

The more famous monument to the Armenian alphabet is located at the exit from Yerevan. It represents images of letters made of tuff, and there is also a statue of Mesrop Mashtots.

In the spiritual capital of Armenia, there is a treasury that is inaccessible to the eyes of ordinary visitors. Here, in an armored safe, two jewelry miracles are kept - 36 classic gold letters and a cross, decorated with precious stones.

This choice is not accidental. The Christian faith and the alphabet played a major role in preserving the national identity of the Armenian people. The treasures were made several decades ago with gold and monetary donations from believers, mostly from the foreign diaspora.

At the top of the hill, at the foot of which the main avenue of Yerevan named after Mashtots ends, there is a monumental gray building. On the basalt wall at the entrance is carved the inscription “Know wisdom and instruction, understand the sayings of the mind.” These were the first words written in Armenian letters. Their author is the monk and educator Mesrop Mashtots. In 405, he created 36 letters, which Armenians have used almost unchanged for 16 centuries. These letters are carved nearby, in front of the majestic sculpture of the inventor. And the gray building is the famous Institute of Ancient Manuscripts Matenadaran, also named after Mashtots and where I really want to go on my next visit to Yerevan.

The alphabet created by Mashtots contained 29 consonants and 7 vowels, shown in the figure. The last 3 letters were added already in the Soviet years. Some linguists consider their addition to be scientifically unfounded.

The initial and final letters of the Mashtots alphabet have a sacred meaning. The word “Astvats” – God – begins with the first letter, and “Christos” – Christ – begins with the last letter. Mashtots' capital letters simultaneously served as numbering functions.

It follows from the figure that the year 2018 in Armenian can be designated as ՍԺԸ (2000 + 10 + 8).

The modern Armenian alphabet has 39 letters, of which 8 letters convey vowel sounds, 30 letters convey consonant sounds, and the letter և (ev or yev) conveys two, often three sounds together. This alphabet was created in 405 by the Armenian educator, scientist and preacher of Christianity Mesrop Mashtots (361-440). It originally had 36 letters, and the letters և ,օ And ֆ appeared later, in particular օ And ֆ - in the 12th century.

The order of the letters of the Armenian alphabet and the approximate sound of the Armenian letters (read from left to right):

Armenian alphabet best reflects the phonetic system of the Armenian language, therefore it does not have diacritics that clarify the pronunciation of letters, which is often found in many modern languages that use, for example, Latin script for writing. The uniqueness of the Armenian alphabet lies in the fact that its letters and their writing have survived to this day almost unchanged. This certainly makes it easier to read ancient manuscripts, inscriptions and study them.

|

| Mesrop Mashtots (361-440) |

History rarely knows the names of the creators of alphabets in ancient times. Mesrop Mashtots is the first historical figure whose creation of a written system is not associated with legend, but is documented. Mashtots is not only the creator of the alphabet, but also a great educator who, unlike other inventors of writing systems, personally opened schools in different provinces of the country and contributed to the spread of literacy, and his mission played an exceptional role in the history of the Armenian people. Considering the exceptional services of Mesrop Mashtots to the Armenian nation, the Armenian Apostolic Church canonized him. The Order of St. Mesrop Mashtots was established in the Republic of Armenia, which is the highest state award awarded for outstanding achievements in the field of culture, education, and social activities.

Mesrop Mashtots was a regional figure, widely known outside of Armenia. He visited many countries during his life and work, and history also credits him with the creation of the Albanian and Georgian alphabets, which is understandably denied by some Georgian scholars. However, the striking similarity of the letters of the Armenian alphabet, the author of which is Mesrop Mashtots, with the ancient Georgian letters, which cannot be a coincidence, clearly indicates the unconditional involvement of Mashtots in the creation of the latter.

Based on the letters of the Armenian alphabet, in ancient times the Armenian number system was used, the principle of which is that capital letters correspond to numbers in the decimal number system:

Ա-1, Բ-2, Գ-3, Դ-4, Ե-5, Զ-6, Է-7, Ը-8, Թ-9, Ժ-10, Ի-20, Լ-30, Խ- 40, Ծ-50, Կ-60, Հ-70, Ձ-80, Ղ-90, Ճ-100, Մ-200, Յ-300, Ն-400, Շ-500, Ո-600, Չ-700, Պ-800, Ջ-900, Ռ-1000, Ս-2000, Վ-3000, Տ-4000, Ր-5000, Ց-6000, Ու-7000, Փ-8000, Ք-9000. The last three letters of the Armenian alphabet, which appeared later, do not have a numerical equivalent.

Numbers in this system are formed by simple addition, for example:

Ռ ՊԾ Ե = 1855 = 1000+800+50+5 .

This number system is still used by the church today. For example, the name of Catholicos of All Armenians Karekin II is written like this: ԳարեգինԲ.

PREFACE

There are dozens (if not hundreds) of writings in the world: some have fallen out of use for various reasons, while others continue to serve people constantly in all areas of their activity. And people, who repeatedly use writing, do not think about what alphabetic signs are, what evolution they went through before becoming what they became, what meaning was originally inherent in them, why such a sequence of letters in the alphabet was taken, and not different. It seems that these questions will never be answered due to the very antiquity of their creation. But human thought, penetrating the secrets of nature, space and the microworld, creating modern air and water ships, satellites, computers, works and other achievements of science and technology, cannot leave aside the monuments of written culture. Every secret eventually becomes a reality... This, however, requires the efforts of scientists of many generations, but the time spent on solving the mystery can range from several years to several centuries, or even more. The reason for this lies not only in the complexity of the problem, but also, in our opinion, in its relevance. After all, many discoveries of physics over the last century are fundamental, but the relevance of many problems generated by the scientific and technological revolution required colossal creative efforts from scientists all over the world. Various scientific disciplines, depending on their relevance, had their own evolution, to some extent influencing each other. A small number of people study the history of written culture, since it is at the intersection of history, archeology, and linguistics. Therefore, it has never been particularly relevant. This, in my opinion, is the main reason why secrets have been kept in it for so long.

The author of these lines was lucky enough to penetrate the secret of the Armenian alphabet, created, as we know, by the brilliant Mesrop Mashtots. A complex world, worldview, and philosophy underlying the Mesropian alphabet were revealed to him. The mechanism itself, the algorithm for creating alphabetic signs by Mashtots, is not very complicated, which confirms the well-known truth - everything ingenious is simple, but the worldview and meaning embedded in the signs, both individually and collectively, are generally very complex. Proof of the correctness of the hypothesis put forward was that with the help of it the author was able to reveal the secrets of other ancient alphabets, which together outlined the contours of a new theory of the origin of ancient alphabets.

This principle of constructing Mesropov’s letters, being very visual, makes it possible for a new student of our alphabet to remember it very quickly. It was this feature of this principle that forced the author to take up writing this book.

The time comes, and the child joyfully picks up the primer in order to, confused by the letters, pronounce the sounds of his native language. Every year, thousands of Armenian children scattered around the world become familiar with the attractive and harmonious Mesropian alphabet in order to use it to learn both the sonorous and rich Armenian language, as well as the complex world around it, the values of science and culture. Many of our compatriots are also joining it, who, by the will of fate, were once deprived of the opportunity to study in their native language in order to satisfy their spiritual hunger and restore gaps in national self-awareness. Many students study the Armenian language and history at departments of Armenian studies in many countries around the world, as well as linguists, historians and diplomats, for whom interest in Armenia has arisen in recent years. If for politicians and diplomats this interest arose due to the rise of the national movement in connection with the fate of Artsakh, then for historians and linguists the reason is different, but also very significant - the emergence of a new theory about the origin of the Indo-Europeans, put forward by famous linguists V. Ivanov and T. Gamkrelidze.

In this book we will briefly and in an accessible form present this principle, which, being interesting in itself and containing a lot of scientific information, allows you to notice the design of all letters, their similarities and differences, ordering and names. All this together contributes to easier memorization of the letters of the Armenian alphabet, which should be of interest to all those who are interested in the history and culture of Armenia. This is all the more important if you consider that sometimes in print, on posters and announcements, fonts are used that do not make it easier, but, on the contrary, make it difficult to read. There are even special ABC books in pictures, which, according to their authors, should make it easier to memorize the alphabet, but have the opposite effect, because the font used in them is very poor. These facts also prompted the author to present the principle he found for constructing the Armenian alphabet in an accessible form, which, in my opinion, should also be of interest to poster and typeface artists. To do this, we will sometimes have to plunge into history, into the atmosphere of that distant time, so that the reader has some idea of the reason and motives for the creation of the Armenian alphabet, as well as glean some information on the history of written culture.

A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE HISTORY OF WRITING

Writing plays a huge role in the development of humanity; it is a powerful engine in the development of science and culture. Thanks to writing, it is possible to use the huge store of knowledge accumulated by humanity in all spheres of its activity. Writing appeared at a certain stage in the development of mankind and has a history of several thousand years. The need to transmit messages over long distances, the need to store and transmit knowledge to next generations, gave rise to writing. Writing was an additional means of communication to sound language. The appearance of writing itself already testified to a qualitative change in thinking, since it required a certain amount of attention and consciousness. Writing was actually a creative human activity. The history of writing is closely connected with the development of language, the history of the people and its culture. Therefore, the study of writing provides new information about language, history and culture, as well as about the relationship and mutual influence of different cultures. The letter went through several stages in its development. These stages are determined by the types of writing, which, in turn, are determined by which elements of the sound language (whole sentences, words, syllables, sounds) served as a unit for designation.

Typically, scientists distinguish the following four types of writing: pictographic, ideographic, syllabic and letter-sound, although there were not always clear boundaries between them, and there were transitional types. When speaking about such letters, one should not imagine the matter as if the transitions from one to another among the same people were smooth and continuous. Rather, on the contrary, they were complex and could be interrupted for a long time. In one case, among some peoples, one type can remain for a long time without degenerating into another (as, for example, hieroglyphs among the Chinese). In another case, the type of writing could be adopted from a more advanced, perfect one and adapt to its language, as the Greeks did by adopting the Phoenician alphabet, modifying and improving it (for the first time in the world, using letters to denote vowel sounds). This does not mean that the Greeks did not have writing before. The European peoples did the same, adopting the Latin alphabet and adapting it to their native language. And not only Europeans - many peoples of the world did the same. A type of writing could also be forcibly imposed by a powerful country on its dependents. Speaking about the emergence of this or that type of writing, we must take into account the very need for writing in a given era. After all, writing in ancient states was in the hands of priests, priests, and there was no need for its wide dissemination among the people.

Armenia, being at the crossroads of events in the ancient civilized world, had all types of writing in its development - pictograms, hieroglyphs, cuneiform and, finally, the alphabet, although there was no smooth transition from one to another. Cuneiform, for example, was adopted from the Assyrians, although it was modified and improved. This was during the so-called “Urartian” period in the history of Armenia. Then, starting with the campaigns of Alexander the Great, the Hellenistic era began, when the Greek alphabet was used everywhere, including in Armenia. There is still debate among scientists: whether there was a pre-Mashtotsev writing system in Armenia, meaning the alphabetic type of writing. There are many ambiguities here. Be that as it may, in the times immediately preceding the life and work of Mashtots, there was no national alphabet in Armenia. Greek and Syriac languages were used in Armenian schools.

HISTORY OF THE ARMENIAN ALPHABET

The history of the creation of the Armenian alphabet is told to us, first of all, by one of Mashtots’ favorite students, Koryun, in his book “The Life of Mashtots” and Movses Khorenatsi in his “History of Armenia”. Other historians have used their information. From them we learn that Mashtots was from the village of Khatsekats in the Taron region, the son of a noble man named Vardan. As a child, he studied Greek literacy. Then, arriving at the court of Arshakuni, the kings of Great Armenia, he entered the service of the royal office and was the executor of the royal orders. The name Mashtots in its oldest form is referred to as Majdots. The famous historian G. Alishan derives it from the root "Mazd", which, in his opinion, "should have had a sacred meaning." The root "mazd", "majd" can be seen in the names Aramazd and Mazhan (Mazh(d)an, with the subsequent drop of the "d"). The last name is mentioned by Khorenatsi as the name of the high priest. It seems to us that A. Martirosyan’s assumption is correct that “the name Mashtots apparently comes from the preferences of the priestly-pagan period of his family. It is known that after the adoption of Christianity by the Armenians, the sons of the priests were given into the service of the Christian church. The famous Albianid family (church dynasty in Armenia - S.B.) was of priestly origin. The Vardan clan could have been of the same origin, and the name Mashtots is a relic of the memory of this." It is undeniable that Mashtots came from a high class, as evidenced by his education and activities at the royal court. Let us now listen to the testimony of Koryun: “He (Mashtots) became knowledgeable and skilled in worldly orders, and with his knowledge of military affairs he won the love of his warriors... And then,... renouncing worldly aspirations, he soon joined the ranks of hermits. After some time he and his students went to Gavar Gokhtn, where, with the assistance of the local prince, he again converted those who had departed from the true faith into the fold of Christianity, “rescuing everyone from the influence of the pagan traditions of their ancestors and the devilish worship of Satan, bringing them into submission to Christ.” This is how his main activity begins , so he entered church history as the second enlightener.To understand the motives of his educational activities, and then the motives for creating the alphabet, one must imagine the situation in which Armenia found itself at that period of its history, its external and internal atmosphere.

Armenia at that time was between two strong powers, the Eastern Roman Empire and Persia. In the 3rd century in Persia, the Arsacids were replaced by the Sassanid dynasty, which intended to carry out religious reform. Under King Shapukh I, Zoroastrianism became the state religion in Persia, which the Sassanids wanted to forcefully impose on Armenia. The answer was the adoption of Christianity by the Armenian king Trdat in 301. In this regard, A. Martirosyan accurately notes: “The conversion of Armenia to Christianity at the end of the 3rd and beginning of the 4th centuries was a response to the religious reform of Iran. In both Iran and Armenia they were introduced by special royal decrees, as an act of political will. In the first case, religion dictated aggression, in the second resistance."

In 387, Armenia was divided between Byzantium and Persia. The Armenian people did not want to put up with this situation. The Armenian Arsacid dynasty sought to restore the integrity of its kingdom. At that time, her only ally was the church, since the Naharars, being strong individually, waged internecine hostility. Thus, the church was the force that could, by becoming a mediator between the nakharars, raise the people.

At this time, the idea of nationalizing Christianity was born. After all, Christianity, which came to Armenia from Mesopotamia under Hellenistic conditions, was in an alien language and incomprehensible to the people. There was a need for national Christian literature in the native language so that it would be understandable to the people. If for a whole century after the adoption of Christianity the church did not need a national written language due to its cosmopolitan nature, then in the new conditions, after the division of the country, the role of the church changed. At this time, it sought to nationalize in order to become a consolidating core in society. It was at this time that the need for a national written language arose.

Thus, the political situation in Armenia forced Mashtots to leave his service at court and become a hermit. He commissioned works against Zoroastrianism from one of the prominent people of his time, Fyodor Momsuetsky. At the same time, he goes to the region of Gokhtn, located in close proximity to Persia and, therefore, more susceptible to its influence. In this regard, A. Martirosyan in his book comes to the following conclusion: “Mashtots leaves the court not out of disappointment, but with a very definite intention - to organize resistance against the growing Persian influence, the strengthening of Zoroastrianism in the part of divided Armenia that came under Persian rule” - and further concludes: “Thus, although Mashtots began his preaching work for the sake of spreading Christianity, however, with the clear intention of fighting against Zoroastrianism, Christianity had already taken root in Armenia and existed as a state religion for a whole century, so there seemed to be no special need to preach Christianity - if not for this question. Christianity had to be given a special direction, to be aroused against Zoroastrianism, a doctrine whose bearer was the hostile Persian state. Religious teaching turned into a weapon." Having ebullient energy, Mashtots saw that his efforts in preaching were not giving the result that he would like. An additional means of combat was needed. This means was to be national literature. According to Koryun, after the mission to Goghtn, Mashtots “decided to take even more care of the consolation of the entire country, and therefore multiplied his continuous prayers, with outstretched hands (raising) prayers to God, shed tears, remembering the words of the apostle, and said with concern: “Great sorrow for me.” and the incessant torment of my heart for my brothers and relatives..."

So, besieged by sad worries, as if in a network of thoughts, he was in the abyss of thoughts about how to find a way out of his difficult situation. It was at this time, apparently, that Mashtots had the idea of creating an alphabet. He shares his thoughts with Patriarch Sahak the Great, who approved his thought and expressed his readiness to help in this matter.

It was decided to convene a council so that the highest clergy would approve the idea of creating a national alphabet. Koryun states: “For a long time they were engaged in inquiries and searches and endured many difficulties, then they announced the constant search for their Armenian king Vramshapuh.” The king, who had previously been outside the country, upon returning to Armenia, found Sahak the Great and Mashtots together with the bishops, concerned about finding the Armenian alphabet. Here the king told those gathered that while in Mesopotamia, he learned from the priest Abel a certain Syrian bishop Daniel, who had Armenian letters. This Daniel seemed to have unexpectedly found the forgotten old letters of the Armenian alphabet. Having heard this message, they asked the king to send a messenger to Daniel so that he would bring them these letters, which was done. Having received the desired letters from the messenger, the king, together with Catholicos Sahak and Mashtots, were very happy. Youths from all places were gathered to learn new letters. After their training, the king ordered that the same letters be taught everywhere. Koryun narrates: “For about two years, Mashtots was teaching and taught classes in these scripts. But... it turned out that these scripts were not sufficient to express all the sounds of the Armenian language.” After which these letters are discarded. This is the history of the so-called Daniel letters, which, unfortunately, were not preserved in the chronicles and therefore cause a lot of misunderstandings among scientists. Firstly, the dispute is about the meaning of the phrase “suddenly found”. Were these really “forgotten Armenian letters” or did he confuse them with Aramaic (in the letter the words Armenian and Aramaic are written almost identically in Syriac). R. Acharyan believes that this could be an ancient Aramaic letter, which was no longer used in the 4th-5th centuries. These are all assumptions that do not clarify the picture. The very interesting hypothesis about S. Muravyov’s Danilov letters, which will be discussed later, did not clarify the picture either.

Let’s leave Daniel’s letters, to which we will return, and follow Mashtots’ further actions. Movses Khorenatsi narrates that “Following this, Mesrop himself personally goes to Mesopotamia, accompanied by his disciples to the mentioned Daniel, and, not finding anything more former from him,” decides to independently deal with this problem. For this purpose, he, being in one of the cultural centers - in Edessa, visits the Edessa Library, where, apparently, there were ancient sources about writing, about their principles of construction (this idea seems convincing, since in principle, proposed for trial readers, the oldest view is seen in the writings). After searching for a certain time for the necessary principle and graphics, Mashtots finally achieves his goal and invents the alphabet of the Armenian language, and, adhering to the ancient secret principles of creating alphabets, he improved them. As a result, he created an original, perfect alphabet both from the point of view of graphics and from the point of view of phonetics, which is recognized by many famous scientists. Even time could not significantly affect him.

Mashtots describes the very act of creation of the Khorenatsi alphabet in his “History” as follows: “And (Mesrop) sees not a vision in a dream or a waking dream, but in his heart, with pre-spiritual eyes presenting to him the right hand writing on a stone, for the stone kept the markings, like footprints in the snow. And not only (this) appeared to him, but all the circumstances were collected in his mind, as in a certain vessel." Here is an amazing description of Mashtots' moment of insight (it is known that insight accompanies a creative discovery that occurs at the moment of the highest tension of the mind). It is similar to cases known in science. This description of a creative discovery that occurs at the moment of greatest tension of the mind through insight is similar to cases known in science, although many researchers have interpreted it as a direct divine suggestion to Mesrop. A striking example for comparison is the discovery of the periodic table of elements by Mendeleev in a dream. From this example, the meaning of the word “vessel” in Khorenatsi becomes clear - this is a system in which all the letters of the Mesropian alphabet are collected. In this regard, it is necessary to emphasize one important idea: if Mashtots made a discovery (and there is no doubt about this) and the entire table with letters appeared before him, then, as in the case of the periodic table, there must be a principle connecting all the letter signs into a logical system. After all, a set of incoherent signs, firstly, is impossible to open, and, secondly, does not require a long search. And further. This principle, no matter how individual and subjective it may be, must correspond to the principles of constructing ancient alphabets and, therefore, reflect the objective evolution of writing in general and alphabets in particular. This is precisely what some researchers did not take into account when they argued that Mashtots’s main merit was that he revealed all the sounds of the Armenian language, but graphics and signs have no meaning. A. Martirosyan even cites a case when the Dutch scientist Grott asked one nine-year-old girl to come up with a new letter, which she completed in three minutes. It is clear that in this case there was a set of random signs. Most people can complete this task in less time. If from the point of view of philology this statement is true, then from the point of view of the history of written culture it is wrong.

So, Mashtots, according to Koryun, created the Armenian alphabet in Edessa, arranging and giving names to the letters. Upon completion of his main mission in Edessa, he went to another Syrian city of Samosat, where he had previously sent some of his students to master the Greek sciences. Koryun reports the following about Mashtots’ stay in Samosat: “Then... he went to the city of Samosat, where he was received with honors by the bishop of the city and the church. There, in that same city, he found a certain calligrapher of Greek writing named Ropanos, with the help of whom designed and finally outlined all the differences in letters (letters) - thin and bold, short and long, separate and double - and began translations together with two men, his disciples... They began translating the Bible with the parable of Solomon, where at the very beginning he (Solomon) offers to know wisdom." From this story, the purpose of visiting Samosat becomes clear - the newly created letters had to be given a beautiful appearance according to all the rules of calligraphy. From the same story we know that the first sentence written in the newly created alphabet was the opening sentence of the book of proverbs: “Know wisdom and instruction, understand sayings.” Having finished his business in Samosat, Mashtots and his students set off on the return journey.

At home he was greeted with great joy and enthusiasm. According to Koryun, when the news of the return of Mashtots with new writings reached the king and the Catholicos, they, accompanied by many noble nakharars, set out from the city and met the blessed one on the banks of the Rakh River (Araks - S.B.). "In the capital - Vagharshapat this joyful the event was solemnly celebrated.

Immediately after returning to his homeland, Mashtots began vigorous activity. Schools were founded with teaching in the Armenian language, where young men from various regions of Armenia were accepted. Mashtots and Sahak the Great began translation work, which required enormous effort, given that they were translating fundamental books of theology and philosophy. At the same time, Mashtots continued his preaching activities in various regions of the country. Thus, with enormous energy, he continued his activities in three directions for the rest of his life. This is the brief history of the creation of the Armenian alphabet.

THE MAIN MISTAKE OF ARMENIAN ALPHABET RESEARCHERS

Many Armenologists have studied the problem of the origin of the Armenian alphabet. Until recently, many researchers believed that Mashtots did not create, but modified the signs of the Greek (possibly Syrian) alphabet, which, as if summing up this point of view, is said by the late academician E. Aghayan in the book “Mesrop Mashtots”. “Almost all Armenianists who have ever dealt with the issue of creating the Mesropian alphabet were interested in the question of which letters, which alphabet, Mesrop built his letters by modifying.” It is here, in our opinion, that the error lies, which, having become a dogma, has not allowed many researchers to advance towards the truth. Here, for the sake of fairness, it should be noted that in the mentioned book by E. Aghayan it is correctly noted that “The graphic forms of the letters of the Mesropian alphabet represent a certain system, and this system reflects certain graphic principles,” but then, for some unknown reason, it is stated “... and the principles , which are of the most general nature, we find precisely in the form of the letter ¦ (?). The above statement raises deep doubts. It is not clear how it is possible, by modifying the letters of an alphabet, to obtain as a result an original alphabet (here we mean the graphics of letters), moreover, it also represents a system built according to certain graphic principles. It seems that researchers were misled by the slight similarity of some equivalent letters of the Greek and Armenian alphabets. That the styles of Armenian letters represent a system reflecting certain graphic principles, then this really is the case, and the real The work aims to show the principles of letter construction discovered by the author, which are subject to a strict pattern, the random nature of which is excluded and, therefore, it must correspond to Mashtots’ creative plan. Moreover, these principles and patterns are not only graphic, but also philosophical. Moreover, looking ahead, we can say that philosophical principles, as it were, predetermined the graphic ones. Before moving on to the presentation of this principle, let us mention one hypothesis that gave impetus to its disclosure. In the second issue of the magazine "Literary Armenia" for 1985. The work of the Moscow philologist S. Muravyov, “The Mystery of Mesrop Mashtots,” was published, which presents the patterns he discovered in the part of Armenian letters that have a Greek equivalent (it is known that the order of Armenian letters that have a Greek equivalent coincides with the orders of the Greek alphabet). This gave him the opportunity to put forward a hypothetical table of the “letters of Daniel.” S. Muravyov derives the missing letters of the Mesropian alphabet from the signs of this table with the help of changes and various deformations, thereby unwittingly becoming an adherent of the “modification theory”. In fact, S. Muravyov put forward two hypotheses about Danilov’s and Mesrop’s writings, and the supposed table of Danilov’s signs seemed so artificial to him that he decided that it was not an alphabet, but a secret writing. Critics of S. Muravyov believe that his reasoning is far-fetched, because there is no trace left of Daniel’s letters in historiography. Regarding the far-fetchedness, we can say that S. Muravyov did not take these signs out of thin air, but derived them from our alphabet, and not arbitrarily, but from those letters that have a Greek equivalent and in which there are patterns. We cannot ignore this fact. As for S. Muravyov’s second hypothesis about Mesropov’s writings, this work fundamentally refutes it.

PRINCIPLE OF CONSTRUCTING THE ARMENIAN ALPHABET

Upon careful examination of the Armenian letters, both the similarity and the distinctive feature between some of them are striking. For example, Ա, Մ, Ս have a common sign U, but the difference is the dashes in the first two of them. A similar picture is observed in the letters Բ, Ը, Ր. Anyone who first became acquainted with our alphabet noticed these similarities in these letters, as well as in some others. It is obvious that the given letters are formed from two elements - in the first three the common element is U, in the second three - Ր, and the second elements are dashes. We will call the first elements primary, and the second secondary. An observant person should have the following questions: why are some letters constructed according to the indicated method, while others are not, how are other letters constructed, is there any connection, a pattern between all the letter signs? In general, did Mashtots adhere to any principle or algorithm when creating the alphabet? We justified at the top that there must be a principle that would cover all the letters, connecting them logically into a single system. All that remains is to move on to show it...

In order for the reader to be interested in further acquaintance with the material presented, let him pause for a while and try to independently, as far as possible, get closer to the truth. To do this, we will give a specific task-instruction, namely: let him try to group all the letters of the alphabet into basic elements and count their number.

As a detailed analysis showed, all 36 Mesropov letters consist of two types of elements - primary and secondary, that is, the entire alphabet is constructed according to a principle, the essence of which we will indicate a little later.

So, let's move on to grouping letters by basic elements. The following picture emerges:

Ի (main element I),

Լ, Վ (main element Լ),

Ե, Կ, Ն (main element),

Բ, Ը, Ր, մ (basic element Ր),

Գ, Դ, Ղ, Պ (main element),

Ժ (main element J),

Ա, Մ, Ս (basic element U),

Թ, Ռ, Ո (basic element Ո),

t, Ք, Խ, Ի, Հ, Ճ, Ջ (main element),

Զ, Ծ, Փ, Չ, Շ, Ց, Ձ, Ֆ (basic element Օ):

Here it must be emphasized that we have given the most ancient forms of Armenian letters, most of which are indicated in the work of the famous linguist Gr. Acharyan "Armenian letters". This form is known as "erkatagir" - iron writing. For clarity, let’s write down the groups of basic elements one below the other in increasing order of their number:

In the fifth group (counting from above) there is an element different from the rest, and the sixth group is formed from identical pairs. These differences from the general pattern for groups are not accidental, but have their own explanation, which we will give when indicating the deep meaning inherent in all these groups. Taking into account the secondary elements, our triangle takes the following form:

Here the reader should have a legitimate question: if, indeed, Mesrop Mashtots conceived this quantitative relationship between the basic elements of letters (1: 2: 3: 4: 5: 6: 7: 8), then why did such a thing happen in the fifth and sixth groups? metamorphosis? Let us immediately emphasize that when constructing this triangle, not only the mathematical, but also the philosophical principle was taken into account, which predetermined the mathematical and graphic ones.

Each group in this triangle, in our opinion, symbolizes the philosophical categories of antiquity, first developed by the brilliant Aristotle. Let us recall that categories in philosophy are the basic concepts that allow us to better understand the world around us. In the time of Mashtots, as well as in the time of Aristotle, the following eight were considered philosophical categories: place, position, quantity, possession, quality, relation, essence and time, to which Mashtots accordingly correlated the groups of basic elements in the triangle (from top to bottom). In this case, the location of the main elements in the fifth and sixth (counting from the top) lines of the triangle becomes clear - they reflect the specifics of the categories to which, by assumption, they belong - qualities and relationships. Speaking about the category of quality, Aristotle noted that “one of the main properties of quality is that it has an opposite, or if one of the opposites is quality, then the other will also be quality.” In our case, the element J is the opposite of the element . From the first of them the letter d is formed (the numerical value of which is 10). Tens begin with it (a new quality), it is the basis of the decimal number system. Therefore, according to this definition of quality, the basic element has the property of quality. As for the category of relation, when it is taken into account, the alternation of elements U and Ո in the sixth row of the triangle becomes clear. We also find confirmation of what has been said in mathematics: by substituting the numerical values of the corresponding letters in this line, we obtain order ratios: (1:9), (200:600), (1000:2000) (units, hundreds, thousands). Let us emphasize once again that this triangle shows, first of all, the quantitative relationship of the basic elements used in the alphabet. The ordering of the alphabet will be discussed separately.

There are five secondary elements, which symbolize the philosophical elements - earth, water, air, fire and ether. The first four lines are taken from the ancient hieroglyph denoting the World Tree - the oldest cosmological model, according to which the world consists of three layers: air, earth, and water, which are supported by a pillar of fire. The origins of this cosmological concept go back to ancient times, to primitive culture. It is reflected both in religions and in philosophy. In the Bible, for example, the universe is presented in three parts. The book of Exodus (chapter 20, p. 4) speaks of “the heavens above, the earth below, and the waters below the earth.” In "ancient philosophy, the primary bodies (elements) are earth, water, air and fire. Later, a fifth element was added - ether. Ether was considered the primary element. According to Aristotle, the elements of earth, water, air and fire can be obtained from one another, but the given sequence is the shortest path to this transformation.

It is interesting that in S. Muravyov’s hypothetical table of Danilov’s letters the lines correspond to this sequence. By the way, in one of the Matenadaran manuscripts, according to P. Poghosyan, the four columns of the Armenian alphabet (starting from the left) are called fire, air, water and earth, respectively, where the sequence of elements, compared to the previous one, is reversed. This is because when the lines are rotated 90 degrees clockwise, their order is reversed. These facts not only speak in favor of the author’s theory and S. Muravyov’s hypothesis about Danilov’s letters, but also indicate that there is an organic connection between them. This connection is manifested in a detailed analysis of the order of the alphabet, which will be shown directly when considering the ordering of letters.

The sign for the fifth element (ether) was taken by Mashtots, apparently, from the Armenian hieroglyph, which, according to G. Acharyan, means “prosphora” (“նշխար”). In letters, it takes on different positions, which confirms its name (ether translated from Greek means “eternally running”).

In the letters Ի, Լ, Ր, Ս, Ո, Ք, Խ, Ց, the secondary element “fire” merges with the main one. The same action takes place in the letters Հ, Ի with the secondary element “earth.” Let us emphasize that the principle of constructing the Mesropian alphabet is that the alphabetic signs consist of two dissimilar elements. Moreover, the letters themselves are formed: 1) by a simple connection of these elements (in the first six groups of our triangle), 2) by such a connection in which one (or both) of the connecting elements is rotated around its center of rotation, which we observe in some letters of the last two triangle groups. In addition, in the last two groups some basic elements are slightly truncated. All these methods of combining elements are associated with a complex philosophical worldview, which we do not present so as not to complicate the assimilation of the material. But this will not prevent readers from understanding the meaning of the proposed principle.

So the proposed principle should be clear. In the first six groups, the letters are formed by a simple connection; there are no difficulties here, except for the letters Ա and Թ. In these letters, the secondary elements are bent respectively into a broken line and an arc, and in such a way that, firstly, the point of contact of the secondary element with the main one is the same, secondly, the direction of the free end of this element is, if possible, the same, and, in -third, their lengths are also preserved:

![]()

Let us now move on to the seventh group, symbolizing the category of essence. Apparently, there are seven letters in it, the letter Է is the seventh in the alphabet and its numerical value is 7. This number was revered in ancient times as magical, it was considered the essence of all living and non-living things. The letter Ք is the sign of Christ (chrisma) (that is why Mashtots ends his alphabet with it, as if consecrating the letters with a divine sign). The letter Խ is formed from the letter Ք by rotating the latter 90 degrees clockwise and opening the circle (as pointed out by S. Muravyov). In general, in this group, four letters are formed by rotation, and in such a way that the sum of these rotations is equal to zero:

The most difficult thing is to form the letter Ջ. It is obtained by rotating the Ճ sign 135 degrees counterclockwise and replacing the triangle with a rhombus. Then, one secondary element of ether is attached to these signs. In the letter Ճ, there are thus two secondary elements - “water” and “ether”, but since ether was considered primary, it seems to cover another element and the letter Ճ belongs to the ether group.

In the eighth group, in the letters Ձ, Չ, Շ, the secondary elements are slightly rotated, and in the letter Ց a small circle is added on top, the reason for which is not entirely clear. Perhaps this is a kind of compensation for the cross sections in these letters (and in the letter Յ). The letter Շ uses two elements of ether. Why? Because all quantitative relationships both between the primary elements and between the secondary ones must be harmonious. Because, according to ancient philosophers, everything in nature is created according to the laws of harmony. All relationships must be harmonious and correspond to certain proportions. We have shown that there is harmony between the quantities of basic elements. Now let's see what relationship exists between the secondary elements; first, let's listen to Plato's statement on this matter. According to Plato, the creator established between the primary elements “the most precise relationships possible, so that air relates to water as fire relates to air, and water relates to earth as air relates to water.” This is how the body of the cosmos and its soul were created. Man, like all living things, and his soul are created in the image and likeness of the cosmos and his soul and, therefore, has the same beautiful relationships between parts as their prototype. To check Platonic proportions for our case, let's group the letters by philosophical elements. For the elements air, water, earth, fire and ether, the following sequence of numbers is obtained, respectively: 2, 4, 8, 9, 14.