Which language group does the Uzbek language belong to? History of the emergence and development of the Uzbek language. An excerpt characterizing the Uzbek language

, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Russia, Turkey, China, etc.

Spread of the Uzbek language. Blue - to a greater extent, blue - to a lesser extent.

Grammatically and lexically, the closest modern relatives of literary Uzbek are officially the Uyghur and Ili-Turkic languages of the Karluk (Chagatai) group. However, in fact, the Uzbek language is the result of an Oghuz-Karluk synthesis with a predominance of Oghuz phrases, which is especially noticeable when compared with Uyghur [ ] .

Modern literary Uzbek, based on the dialects of the Fergana Valley, is characterized by a lack of vowel harmony. In the 20s of the 20th century, attempts were made to artificially consolidate vowel harmony in the literary language, which was preserved only in peripheral dialects (primarily Khorezm). In phonetics, grammar and vocabulary there is a noticeable strong substrate influence of Perso-Tajik, which dominated in Uzbekistan until the 12th-13th centuries, and still has a certain distribution. There is also the influence of another Iranian language, Sogdian, which was dominant before the Islamization of Uzbekistan. Most Arabisms in the Uzbek language were borrowed through Perso-Tajik. Since the mid-19th century, the Uzbek language has been heavily influenced by the Russian language.

Story

The formation of the Uzbek language was complex and multifaceted.

Largely thanks to the efforts of Alisher Navoi, Old Uzbek became a unified and developed literary language, the norms and traditions of which were preserved until the end of the 19th century. At the beginning of the 20th century. In the Uzbek literary language, a tendency has emerged to democratize its norms, as a result of which it has become simpler and more accessible.

Until the beginning of the 20th century. on the territory of the Bukhara Khanate and the Khorezm (Khiva) state, the literary languages were Persian and Chagatai (Old Uzbek). Since the beginning of the 20th century, mainly through the efforts of supporters of Jadidism (Fitrat, Niyazi, etc.), a modern literary language has been created based on the Fergana dialect.

The term “Uzbek” itself, when applied to the language, had different meanings at different times. Until 1921, “Uzbek” and “Sart” were considered two dialects of the same language. At the beginning of the 20th century, N.F. Sitnyakovsky wrote that the language of the Sarts of Fergana is “purely” Uzbek (Uzbek-tili). According to the Kazakh Turkologist Seraly Lapin, who lived at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, “there is no special Sart people different from the Uzbeks, and there is no special Sart language different from the Uzbek.” Others divided the Sarts and the Uzbeks.

Dialects

The modern Uzbek language has a complex dialect structure and occupies a unique place in the classification of Turkic languages. The dialects of modern spoken Uzbek are genetically heterogeneous (speakers of the Karluk, Kipchak, Oguz dialect groups participated in their formation), conditionally divided on a phonetic basis into 2 groups - “local” (dialects of the cities of Tashkent, Samarkand, Bukhara, etc. and adjacent areas) and “ accusatory” (divided into two subgroups depending on the use of the initial consonant “y” or “j”);

There are four main dialect groups.

- Northern Uzbek dialects of southern Kazakhstan (Ikan-Karabulak, Karamurt, probably belong to the Oghuz group).

- Southern Uzbek dialects of the central and eastern parts of Uzbekistan and northern Afghanistan, as well as the dialects of most large centers of settlement of Uzbeks (Tashkent, Ferghana, Karshi, Samarkand-Bukhara and Turkestan-Chimkent) belong to the Karluk (Chagatai), or southeastern group of Turkic languages ; on this basis, it is customary to include the Uzbek language as a whole, together with Uyghur. The Fergana and Turkestan-Chimkent dialects are closest to the literary norm. The pronunciation standard is assigned to the Fergana-Tashkent group of dialects (after 1937).

The main feature of these dialects is that they are more or less Iranianized. The long-lasting influence of Iranian dialects (mainly the Tajik language) is strongly noticeable here not only at the lexical, but also at the phonetic levels.

- The Oguz group includes the Khorezm dialect, which is close to the Turkmen language, and other dialects of the south- and north-west of Uzbekistan (as well as two dialects in Kazakhstan) under the general name Oguz dialect. In the classification of A. N. Samoilovich, these dialects are described as Khiva-Uzbek and Khiva-Sartov dialects and are separated into an independent group called Kipchak-Turkmen.

- Kipchak dialects, relatively close to the Kazakh language, are widespread throughout the country, as well as in other Central Asian republics and Kazakhstan. This also includes the Surkhandarya dialect. Historically, these dialects were formed among the nomadic Uzbeks, who by origin were related to the Kazakhs, but were not subjects of the Kazakh Khanate.

Grammar

Unlike most other Turkic languages, Uzbek morphology is characterized by monovariance of affixes (as a result of the absence of synharmonicity).

It does not have a grammatical category of gender: there is no agreement in gender, case and number of the definition and the defined. It is mandatory to agree between the subject and the predicate in person, but not necessarily in number.

There are 6 cases in Uzbek:

- main - zero indicator;

- genitive (attributive) - exponent -ning; draws up the adopted definition;

- dative (directive) - indicator -ga; expresses the direction of action on an object; basically forms an indirect addition;

- accusative - indicator -ni; acts as a direct object;

- local - indicator -da; expresses the place or time of the action, the name acts as a circumstance;

- initial - indicator -dan; basically expresses the object along which (through which, past which, through which) the action is performed.

A noun has a category of belonging (izafet), the forms of which are formed using affixes of belonging, denoting the person of the owner: kitob"book", kitobim"my book", kitobing"your book", kitobi“his (her) book”; uka"Brother", ukam"my brother", ukang"your brother", ukasi his (her) brother; oʻzbek " Uzbek", til"language" - oʻzbek tili"Uzbek language".

Phonetics

Main phonological features: lack of vowel harmony (synharmonism) and okanye.

The law of vowel harmony, characteristic of most Turkic languages, is that a word can contain either only front vowels or only back vowels. In modern Uzbek, common Turkic vowels o And ö correspond to one sound “o”, in spelling - ў (Cyrillic) or oʻ(Latin); u And ü - like Russian "y"; ı And i- like Russian "And". Remnants of vocal synharmonism are preserved only in the Kypchak dialects. “Okanye” consists in the transition in a number of cases of the common Turkic a in or "o", at the same time common Turkic ä more often [

Invention of the concept of “Uzbeks”

Before the national-state demarcation of Soviet Central Asia, such a people as the Uzbeks did not exist. The settled population that lived in this territory was called the collective term “sart,” which in Persian means “trader.” The word “sart” was found in Plano Carpini in the 13th century. However, the concept of “sart” was not so much ethnic as it reflected the economic and cultural type of the settled population of Central Asia. The Sarts called themselves by the name of the area where they lived: Tashkent, Kokand, Khivan, Bukharan, Samarkand...

In addition to the Sarts, the territory of the future Uzbekistan was inhabited by numerous nomadic Turkic tribes, such as Ming, Yuz, Kyrk, Jalair, Sarai, Kongurat, Alchin, Argun, Naiman, Kipchak, Kalmak, Chakmak, Kyrgyz, Kyrlyk, Turk, Turkmen, Bayaut, Burlan, Shymyrchik, kabasha, nujin, kilechi, kilekesh, buryat, ubryat, kyyat, hytay, kangly, uryuz, dzhunalahi, kuji, kuchi, utarchi, puladchi, dzhyyit, juyut, dzhuldzhut, turmaut, uymaut, arlat, kereit, ongut, tangut, Mangut, Jalaut, Mamasit, Merkit, Burkut, Kiyat, Kuralash, Oglen, Kara, Arab, Ilachi, Juburgan, Kyshlyk, Girey, Datura, Tabyn, Tama, Ramadan, Uyshun, Badai, Hafiz, Uyurji, Jurat, Tatar, Yurga, batash, batash, kauchin, tubay, tilau, kardari, sankhyan, kyrgyn, shirin, oglan, chimbay, charkas, uyghur, anmar, yabu, targyl, turgak, turgan, teit, kohat, fakhir, kujalyk, shuran, deradjat, kimat, Shuja-at, Avgan - a total of 93 clans and tribes. The most powerful tribes were the Datura, Naiman, Kunrat and, of course, the Mangyt.

Average Uzbek

Average Uzbek woman

The Mangyts also included a secular dynasty in the Bukhara Emirate, which in 1756 replaced the Ashtarkhanid dynasty - the former Astrakhan khans and ruled until the capture of Bukhara by the Red Army in 1920. Another powerful tribe was the Mings, who formed the ruling dynasty of the Kokand Khanate in 1709.

Son of the last Bukhara emir, Major of the Red Army Shakhmurad Olimov

The last Emir of Bukhara, Alim Khan, from the Mangyt clan

Since the question of what peoples live in Soviet Turkestan did not have a clear answer, a special Commission was created to study the tribal composition of the population of the USSR and neighboring countries. Summing up the results of its work during 1922-1924, the Commission committed an obvious forgery, passing off representatives of various tribes and clans of Turkic-Mongolian origin as historically non-existent ethnic Uzbeks. The Commission appointed Khiva Karakalpaks, Fergana Kipchaks, Samarkand and Fergana Turks as Uzbeks.

At first, Uzbekistan was the same territorial concept as Dagestan, where more than 40 nationalities live, but over several decades the peoples of Central Turkestan managed to drum into it that they were an Uzbek nation.

In 1924, the population of the central part of Central Asia was given the collective name of Uzbeks in honor of Uzbek Khan, who stood at the head of the Golden Horde in 1313-41 and zealously spread Islam among the Turkic tribes subject to him. It is the reign of Uzbek that is considered the starting point of current Uzbek historiography, and some scholars, such as academician Rustam Abdullaev (not to be confused with the famous Moscow proctologist), call the Golden Horde Uzbekistan.

Bukhara zindan

Before the national-state demarcation, the territory of Uzbekistan was part of the Turkestan ASSR as part of the RSFSR, the Bukhara People's Soviet Republic, formed instead of the Bukhara Emirate as a result of the Bukhara operation of the Red Army, and the Khorezm People's Soviet Republic (from October 1923 - Khorezm Soviet Socialist Republic), formed instead of the Khiva Khanate as a result of the Khiva Revolution.

Uzbek customs

Urban Uzbeks are quite normal people. Most of them know Russian, are polite and educated. However, it is not representatives of the Uzbek intelligentsia who go to Russia, but residents of small towns and rural areas, who have a completely different mentality and observe their patriarchal traditions.

It is noteworthy that even in the 21st century, rural Uzbeks have preserved the custom according to which parents find a life partner for a lonely child; personal preferences are strictly secondary. And, since one of the unspoken laws of the Uzbeks is to obey and honor their parents, the son or daughter is forced to meekly agree.

Brides in most regions of Uzbekistan still pay bride price. According to local standards, this is compensation to the girl’s family for her upbringing and for the loss of workers. Often the money that the groom's family gives to the girl's family at the time of the wedding provides for the living of the bride's younger siblings. If, after many years of waving a broom in Russia, they have not been able to save up for the bride price, the bride is simply stolen. The police of Uzbekistan are engaged in the return of the bride only if the parents pay well. But Uzbeks steal brides in other countries too. Thus, in the Osh region of Kyrgyzstan, where many Uzbeks live, a large-scale action against the practice of bride kidnapping was recently held. Activists then came out with information that every year in Kyrgyzstan over ten thousand girls are forced into marriage, half of such marriages subsequently break up, and there have been cases of suicide of kidnapped girls. As a result, bride kidnapping in Kyrgyzstan is now equivalent to kidnapping, and this crime is punishable by imprisonment for a period of 5 to 10 years. Often cases of simple rape are passed off as theft of a bride, and sometimes grooms demand a ransom to return the bride home.

Another deep-rooted Uzbek tradition remains pedophilia. The sexual exploitation of boys in Uzbek is called bacha-bozlik Bacha bazi (in Persian - playing with “calves”), and these boys themselves are called bacha.

Before the annexation of these regions to Russia, the Kokands and Bukharans made frequent raids on Kazakh villages and even Russian villages. The main prey during such raids were boys, who were sold into sexual slavery, and when they began to grow beards, they were simply killed.

In Soviet times, Uzbeks were terribly offended by the fact that in the official speeches of the leaders of the USSR the Russian people were called their elder brother. The fact is that if for us the elder brother is the one who stands up for you in a street fight, then among these peoples the elder brother is the one who has you in the anus. The fact is that in their families they have a clear hierarchy - the father can have all the sons, daughters and daughters-in-law, and the older brother can have all the younger brothers and sisters, as well as the wives of the younger brothers. If younger brothers begin to have nephews - children of older brothers, then they are already punished for this, but, as a rule, not much, but still, fearing punishment, such teenagers rape other people's children, for which, however, they can get severe punishment. Therefore, they either rape very young children who cannot complain, or resort to child prostitution.

Bacha from Samarkand

Child prostitution has deep roots in Uzbekistan. The pimps in it are the parents of minor prostitutes and prostitutes, but if a girl can be sold for good, under the guise of being given in marriage, then the boys have to be rented out.

Traditional farming

By the beginning of the 20th century, there were few purely nomadic groups left among the future Uzbeks: most tribes led a semi-sedentary lifestyle, combining cattle breeding with agriculture. However, their way of life and organization of everyday life remained connected with the pastoral culture. Home crafts for processing livestock products were preserved: tanning, felting, carpet weaving, patterned weaving from woolen threads.

The main dwelling for cattle breeders was the yurt, but even where permanent houses appeared, it was used as an auxiliary and ritual dwelling.

Uzbek men's and women's clothing consisted of a shirt, wide-legged trousers and a robe (quilted with cotton wool or simply lined). The robe was belted with a sash (or a folded scarf) or worn loose. Sometimes the robe was belted with several scarves at once - the number of scarves corresponded to the number of wives of the owner of the robe. Women wore Chavchan, over which they put a burqa.

Uzbek cuisine is characterized by its diversity. The Uzbek food consists of a large number of various plant, dairy, and meat products. An important place in the diet is occupied by bread baked from wheat, less often from corn and other types of flour in the form of various flatbreads (obi-non, patir and others). Ready-made flour products, including dessert ones, are also common. The range of dishes is varied. Dishes such as Lagman, shurpa and porridges made from rice (shawl) and legumes (mashkichiri) are seasoned with vegetable or cow butter, fermented milk, red and black pepper, various herbs (dill, parsley, cilantro, raikhan, etc.) . There are a variety of dairy products - katyk, kaymak, sour cream, cottage cheese, suzma, pishlok, kurt, etc. Meat - lamb, beef, poultry (chicken, etc.), less often horse meat.

Such popular foods as fish, mushrooms and other products occupy a relatively insignificant place in the diet. The favorite dish of Uzbeks is pilaf. Uzbeks also love manta rays.

Uzbek language

The Uzbek language also does not represent something unified. Each of the above tribes spoke its own language or dialect, which even belonged to different linguistic branches of the Turkic languages - Kipchak (which includes Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Bashkir, Nogai, Tatar, Karaite, Karachay-Balkar, Crimean, Urum and Karakalpak), Oguz (which includes Turkish, Turkmen, Gagauz, Afshar and Azerbaijani) and Karluk (Uyghur, Khoton, etc.). At the same time, in the 20s, the Uzbek literary language was artificially created on the basis of the language of the inhabitants of the Fergana Valley. The Ferghana language was taken as a basis not only because it was closest to the extinct Chagatai literary language, which was written in the Timurid era, but also in order to prevent the dominance of the Mangyt language and, accordingly, the Bukharians, who had previously had their own statehood. Here it must be said that the Central Asian intelligentsia had previously used mainly the Tajik language, but after that the New Uzbek language was intensively introduced, prudently cleared of many Tajik borrowings. For the same reason, on September 1, 1930, the capital of the Uzbek SSR was moved from Tajik-speaking Samarkand to Turkic-speaking Tashkent. Until now, in Bukhara and Samarkand, the Uzbek intelligentsia prefers to speak Tajik, not caring about all directives. The speakers of this language are not actually Tajiks at all. These are the so-called chalas (literally “neither this nor that”), who are mainly Bukharian Jews who converted to Islam in appearance. They have almost completely lost elements of Jewish ritual, and they carefully hide their Jewish origin.

A rabbi teaches literacy to Bukharian Jewish children.

(the state language of the country), partly in other Central Asian states of the former USSR, in Afghanistan and the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China. In the USSR, according to the 1989 census, there were about 16.7 million Uzbeks (the third largest ethnic group after Russians and Ukrainians), of which about 16.4 million called Uzbek their native language; there are about 1.2 million Uzbeks in Afghanistan; given the rapid growth of the Uzbek population, current figures are higher; Uzbek is one of the largest Turkic languages along with Turkish and Azerbaijani.

Distributed in the very heart of the Turkic-speaking area, the modern Uzbek language has a complex dialect structure and occupies a unique place in the classification of Turkic languages. The dialects of most large centers of settlement of Uzbeks (Tashkent, Fergana, Karshi, Samarkand-Bukhara and Turkestan-Chimkent) belong to the Karluk, or southeastern group of Turkic languages; on this basis, it is customary to include the Uzbek language as a whole, together with Uyghur. However, modern Uzbek also includes a group of dialects belonging to the Kipchak group (they are widespread throughout the country, as well as in other republics of Central Asia and Kazakhstan); the dialects of Khorezm and a number of adjacent territories in the north-west of the country (and two dialects in Kazakhstan) belong to the Oghuz group.

The Uzbek language, unlike related Turkic languages, is characterized by the absence of synharmonism (similarity of vowels in a word), which is preserved only in Kipchak dialects. In phonetics, grammar and vocabulary, a strong influence of the Persian language is noticeable; The vocabulary also contains numerous Arabic and Russian borrowings.

The Uzbek language has a centuries-old written tradition in the form of the Central Asian Turkic language (Chagatai, or Old Uzbek), which developed in the 15th–16th centuries. based on the Karluk-Uyghur dialects of Transoxiana and which became the official language in Timur’s power. The Old Uzbek language was influenced by the literary language of the Karakhanid state (11th–12th centuries; the so-called Karakhanid-Uyghur language), the Karluk-Khorezmian literary language of the Syr Darya valley (12th–14th centuries; also known as the Khorezm-Turkic language) and Persian literature . The heyday of Turkic-language literature in Central Asia dates back to the 15th–16th centuries; the pinnacle of poetry in the Old Uzbek language is the work of Alisher Navoi (1441–1501; sometimes the language of this period is called Central Uzbek).

The modern literary Uzbek language was formed on the basis of the Fergana-Tashkent group of dialects. Writing in the Uzbek language existed in Arabic until 1930, in 1930–1939 on a Latin basis, and since 1939 on the basis of Russian graphics with some additional letters. A variety of original literature has been created in the Uzbek language. In Uzbek schools, all general education disciplines are taught in it; its use in higher education is expanding; In Russian schools, the Uzbek language is studied as a subject.

The scientific study of the Uzbek language was started by M.A. Terentyev, who published in 1875 in St. Petersburg Turkish, Persian, Kyrgyz and Uzbek grammar. Subsequently, the works of E.D. Polivanov, A.N. Kononov, V.V. Reshetov and other researchers made an important contribution to the study of the Uzbek language.

The history of the emergence and development of the Uzbek language is closely intertwined with the history of its speakers. The emergence of such a nation as the Uzbek people was due to the process of merging a number of ethnic groups, the means of communication of which were Turkic and Iranian languages. This explains the large number of dialects in the Uzbek dialect, between which there is a huge difference.

The history of the development of the Uzbek language can be divided into three stages: the periods of ancient Turkic, old Uzbek and modern languages.

Old Turkic language

This stage dates back to the V-XI centuries. The Turks settled along the banks of the Syr Darya, Amu Darya and Zeravshan, gradually pushing aside the inhabitants of the Indo-Iranian tribes. The means of communication was the ancient Turkic language, on the basis of which many Asian languages were subsequently formed. Today, only fragments of ancient Turkic writing remain, imprinted on cultural monuments dating back to this period.

Starousbek

The second stage dates back to the XI-XIX centuries. During this time, the Uzbek language developed under the influence of many neighboring languages. A huge contribution to the formation of the language was made by the poet Alisher Navoi, who created a unified and developed literary language. It was in this form that it was used until the turn of the 19th century without changes.

Modern Uzbek language

The twentieth century was marked by the beginning of the formation of the modern Uzbek language. It is based on the Fergana dialect, which is generally recognized among all residents of Uzbekistan. Most of the population spoke this dialect, which they knew as the Sart language, and its speakers were called Sarts. Ethnic Sarts did not belong to the Uzbek people, but in the 20s of the last century the word “Sart” was abandoned, and the inhabitants of the country began to be called Uzbeks. The norms of the literary language became more democratic, which made it much simpler and more accessible.

Uzbek writing

Throughout the history of development in the Uzbek language, there have been three different scripts.

From antiquity until the end of the 20s of the last century, the Uzbek ethnic group was based on the Arabic alphabet. With the advent of Soviet power, writing was subjected to a number of reforms. Until 1938, the Latin alphabet was in use, and then they switched to the Cyrillic alphabet, which lasted until 1993. When the Uzbek Republic became an independent state, the Latin alphabet returned again.

Nowadays, in Uzbek writing, Arabic letters, Latin and Cyrillic alphabet are used in parallel. The older generation prefers Cyrillic graphics, and Uzbeks living abroad prefer Arabic letters. In educational institutions they teach in the Latin alphabet, so it is difficult for pupils and students to read books that were published under Soviet rule.

The Uzbek language is rich in borrowed words from the Persian language. In the 20th century, the vocabulary was significantly enriched with Russian words, and today it is intensively replenished with English borrowings. According to the state program. There is an active cleansing of the language from borrowed words.

All this, naturally, causes special difficulties in learning the Uzbek language and translations, but makes it unique and more interesting.

And other countries. It is dialectical, which allows it to be classified into different subgroups. It is the native and main language of most Uzbeks.

Modern literary Uzbek, based on the dialects of the Fergana Valley, is characterized by a lack of vowel harmony. In the 20s of the 20th century, attempts were made to artificially consolidate vowel harmony in the literary language, which was preserved only in peripheral dialects (primarily Khorezm). In phonetics, grammar and vocabulary there is a noticeable strong substrate influence of Perso-Tajik, which dominated in Uzbekistan until the 12th-13th centuries, and still has a certain distribution. There is also the influence of another Iranian language, Sogdian, which was dominant before the Islamization of Uzbekistan. Most Arabisms in the Uzbek language were borrowed through Perso-Tajik. Since the mid-19th century, the Uzbek language has been heavily influenced by the Russian language.

Story

The formation of the Uzbek language was complex and multifaceted.

The Old Uzbek language was influenced by the literary language of the Karakhanid state (XI-XII centuries; the so-called Karakhanid-Uighur language), the Karluk-Khorezm literary language of the Syr Darya valley (XII-XIV centuries; also known as the Khorezm-Turkic language), Oguz- Kipchak literary language and Persian literature. The flourishing of the old Uzbek literary language is associated with the work of the founder of Uzbek classical literature Alisher Navoi (1441-1501), Zahir ad-din Muhammad Babur (1483-1530) and other poets. The language of this period is sometimes also called Central Uzbek.

Largely thanks to the efforts of Alisher Navoi, Old Uzbek became a unified and developed literary language, the norms and traditions of which were preserved until the end of the 19th century. At the beginning of the 20th century. In the Uzbek literary language, a tendency has emerged to democratize its norms, as a result of which it has become simpler and more accessible.

Until the beginning of the 20th century. on the territory of the Bukhara Khanate and the Khorezm (Khiva) state, the literary languages were Persian and Chagatai (Old Uzbek). Since the beginning of the 20th century, mainly through the efforts of supporters of Jadidism (Fitrat, Niyazi, etc.), a modern literary language has been created based on the Fergana dialect.

Dialects

The modern Uzbek language has a complex dialect structure and occupies a unique place in the classification of Turkic languages. The dialects of modern spoken Uzbek are genetically heterogeneous (speakers of the Karluk, Kipchak, Oguz dialect groups participated in their formation), conditionally divided on a phonetic basis into 2 groups - “local” (dialects of the cities of Tashkent, Samarkand, Bukhara, etc. and adjacent areas) and “ accusatory” (divided into two subgroups depending on the use of the initial consonant “y” or “j”);

There are four main dialect groups.

- Northern Uzbek dialects of southern Kazakhstan (Ikan-Karabulak, Karamurt, probably belong to the Oguz group).

- Southern Uzbek dialects of the central and eastern parts of Uzbekistan and northern Afghanistan, as well as the dialects of most large centers of settlement of Uzbeks (Tashkent, Ferghana, Karshi, Samarkand-Bukhara and Turkestan-Chimkent) belong to the Karluk (Chagatai), or southeastern group of Turkic languages ; on this basis, it is customary to include the Uzbek language as a whole, together with Uyghur. The Fergana and Turkestan-Chimkent dialects are closest to the literary norm. The pronunciation standard is assigned to the Fergana-Tashkent group of dialects (after 1937).

The main feature of these dialects is that they are more or less Iranianized. The long-lasting influence of Iranian dialects (mainly the Tajik language) is strongly noticeable here not only at the lexical, but also at the phonetic levels.

- The Oguz group includes the Khorezm dialect, which is close to the Turkmen language, and other dialects of the south- and north-west of Uzbekistan (as well as two dialects in Kazakhstan) under the general name Oguz dialect. In the classification of A. N. Samoilovich, these dialects are described as Khiva-Uzbek and Khiva-Sartov dialects and are separated into an independent group called Kipchak-Turkmen.

- Kipchak dialects, relatively close to the Kazakh language, are widespread throughout the country, as well as in other Central Asian republics and Kazakhstan. This also includes the Surkhandarya dialect. Historically, these dialects were formed among the nomadic Uzbeks, who by origin were related to the Kazakhs, but were not subjects of the Kazakh Khanate.

Grammar

Unlike most other Turkic languages, Uzbek morphology is characterized by monovariance of affixes (as a result of the absence of synharmonicity).

It does not have a grammatical category of gender: there is no agreement in gender, case and number of the definition and the defined. It is mandatory to agree between the subject and the predicate in person, but not necessarily in number.

There are 6 cases in Uzbek:

- Basic - zero indicator

- genitive (attributive) - exponent -ning; draws up the accepted definition

- dative (directive) - indicator -ga; expresses the direction of action on an object, mainly forms an indirect object

- accusative - indicator -ni; acts as a direct complement

- local - indicator -da; expresses the place or time of the action, the name acts as a circumstance

- initial - indicator -dan; basically expresses the object along which (through which, past which, through which) the action is performed

A noun has a category of belonging (izafet), the forms of which are formed using affixes of belonging, denoting the person of the owner: kitob- book, kitobim- my book, kitobing- your book, kitobi- his (her) book; uka- Brother, ukam- my brother, ukang- your brother, ukasi- his (her) brother; oʻzbek- Uzbek, til- language, oʻzbek tili- Uzbek language.

Phonetics

Main phonological features: lack of vowel harmony (synharmonism) and okanye. The law of vowel harmony, characteristic of most Turkic languages, is that a word can contain either only front vowels or only back vowels. In modern Uzbek, common Turkic vowels o And ö correspond to one sound o, in spelling ‹ў› (Cyrillic) or ‹oʻ› (Latin), u And ü - u(Kir. ‹у›), and ı And i - i(Kir. ‹и›). Remnants of vocal synharmonism are preserved only in the Kypchak dialects. “Okanye” consists in the transition in a number of cases of the common Turkic a in or ‹о›, at the same time common Turkic ä often implemented as a simple a.

Other features: lack of primary long vowel sounds. Secondary (substitute) longitudes appear as a result of the loss of a consonant sound adjacent to the vowel. Phonetic ultralongitude or emphatic lengthening of individual vowels is observed. There is no division of affixes into front and back.

Vocabulary

The basis of the vocabulary of the modern literary Uzbek language is made up of words of common Turkic origin. However, unlike the neighboring Kipchak languages, the Uzbek vocabulary is rich in Persian (Tajik) and Arabic borrowings. The influence of the Russian language is noticeable in the surviving significant layer of everyday, socio-political and technical vocabulary that came from the conquest of Turkestan by Tsarist Russia (the second half of the 19th century) to the present time, especially during the Soviet era (until 1991).

Writing

Until 1928, the Uzbek language used the Arabic alphabet. From until the 1940s, the USSR used a writing system based on the Latin alphabet. From 1992 to 1992, the USSR used the Cyrillic alphabet. In 1992, the Uzbek language in Uzbekistan was again translated into the Latin alphabet (despite the reform to translate the Uzbek language into the Latin script, in fact, the parallel use of the Cyrillic and Latin alphabet continues at present), which, however, differs significantly from both the 1928 alphabet and and from modern Turkic Latin scripts (Turkish, Azerbaijani, Crimean Tatar, Turkmen, etc.). In particular, in the modern Uzbek alphabet used in Uzbekistan, for the purpose of unification with the main Latin alphabet, there are no characters with diacritics, while the 1928 alphabet used not only characters with diacritics, but also unique characters invented by Soviet linguists specifically for the languages of small peoples of the USSR. For example, the sounds [w] and [h] are now designated in the same way as in English. In Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, the Uzbek language uses an alphabet based on the Cyrillic alphabet, and in Afghanistan, an alphabet based on the Arabic script.

Features of transliteration of Uzbek proper names

The transliteration of Uzbek personal names and geographical names traditionally accepted in Russian has two features. The first is the non-reflection of Western dialects in Uzbek writing that has survived since pre-revolutionary times. For example, Uzbek names and titles, in the Russian tradition transmitted as Bekabad, Andijan, written in Uzbek Bekobod, Andijon. These words contain a sound that is more closed than [a], but more open than [o].

The second feature is the tradition that appeared under the influence of the Uzbek Cyrillic alphabet to convey the sound [o] in many words, which was designated in Cyrillic by the letter ў , through at due to the similarity of the corresponding letters: Uzbekistan - Uzbekistan(Oʻzbekiston). In fact, these words contain a sound that is more closed than [o], but more open than [u].

Geographical distribution

see also

- Chagatai language (Old Uzbek)

Write a review about the article "Uzbek language"

Notes

Literature

- Baskakov N. A. Historical and typological phonology of Turkic languages / Rep. ed. corresponding member USSR Academy of Sciences E. R. Tenishev. - M.: Nauka, 1988. - 208 p. - ISBN 5-02-010887-1.

- Ismatullaev Kh. Kh. Self-teacher of the Uzbek language. - Tashkent: Okituvchi, 1991. - 145 p.

- Kononov A. N. Grammar of the modern Uzbek literary language. - M., L.: Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 1960.

- Khodzhiev A.P. Uzbek language // Languages of the world: Turkic languages. - M.: Institute of Linguistics of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 1996. - P. 426-437. - (Languages of Eurasia). - ISBN 5-655-01214-6.

- Boeschoten, Hendrik. Uzbek // The Turkic Languages / Edited by Lars Johanson and Éva Á. Csató. - Routledge, 1998. - pp. 357-378.

- Johanson, Lars. Uzbek // / Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie. - Elsevier, 2009. - pp. 1145-1148. - ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7.

Links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

An excerpt characterizing the Uzbek language

Having caught up with the guards infantry, he noticed that cannonballs were flying through and around them, not so much because he heard the sound of cannonballs, but because he saw concern on the faces of the soldiers and unnatural, warlike solemnity on the faces of the officers.Driving behind one of the lines of infantry guard regiments, he heard a voice calling him by name.

- Rostov!

- What? – he responded, not recognizing Boris.

- What is it like? hit the first line! Our regiment went on the attack! - said Boris, smiling that happy smile that happens to young people who have been on fire for the first time.

Rostov stopped.

- That's how it is! - he said. - Well?

- They recaptured! - Boris said animatedly, having become talkative. - You can imagine?

And Boris began to tell how the guard, having taken their place and seeing the troops in front of them, mistook them for Austrians and suddenly learned from the cannonballs fired from these troops that they were in the first line, and unexpectedly had to take action. Rostov, without listening to Boris, touched his horse.

- Where are you going? – asked Boris.

- To His Majesty with an errand.

- Here he is! - said Boris, who heard that Rostov needed His Highness, instead of His Majesty.

And he pointed him to the Grand Duke, who, a hundred paces away from them, in a helmet and a cavalry guard's tunic, with his raised shoulders and frowning eyebrows, was shouting something to the white and pale Austrian officer.

“But this is the Grand Duke, and I should go to the commander-in-chief or the sovereign,” said Rostov and started to move his horse.

- Count, count! - shouted Berg, as animated as Boris, running up from the other side, - Count, I was wounded in my right hand (he said, showing his hand, bloody, tied with a handkerchief) and remained in the front. Count, holding a sword in my left hand: in our race, the von Bergs, Count, were all knights.

Berg said something else, but Rostov, without listening to him, had already moved on.

Having passed the guards and an empty gap, Rostov, in order not to fall into the first line again, as he came under attack by the cavalry guards, rode along the line of reserves, going far around the place where the hottest shooting and cannonade was heard. Suddenly, in front of him and behind our troops, in a place where he could not possibly suspect the enemy, he heard close rifle fire.

"What could it be? - thought Rostov. - Is the enemy behind our troops? It can’t be, Rostov thought, and a horror of fear for himself and for the outcome of the entire battle suddenly came over him. “Whatever it is, however,” he thought, “there’s nothing to go around now.” I must look for the commander-in-chief here, and if everything is lost, then it’s my job to perish along with everyone else.”

The bad feeling that suddenly came over Rostov was confirmed more and more the further he drove into the space occupied by crowds of heterogeneous troops, located beyond the village of Prats.

- What's happened? What's happened? Who are they shooting at? Who's shooting? - Rostov asked, matching the Russian and Austrian soldiers running in mixed crowds across his road.

- The devil knows them? Beat everyone! Get lost! - the crowds of people running and not understanding, just like him, what was happening here, answered him in Russian, German and Czech.

- Beat the Germans! - one shouted.

- Damn them - traitors.

“Zum Henker diese Ruesen... [To hell with these Russians...],” the German grumbled something.

Several wounded were walking along the road. Curses, screams, moans merged into one common roar. The shooting died down and, as Rostov later learned, Russian and Austrian soldiers were shooting at each other.

"My God! what is this? - thought Rostov. - And here, where the sovereign can see them at any moment... But no, these are probably just a few scoundrels. This will pass, this is not it, this cannot be, he thought. “Just hurry up, pass them quickly!”

The thought of defeat and flight could not enter Rostov’s head. Although he saw French guns and troops precisely on Pratsenskaya Mountain, on the very one where he was ordered to look for the commander-in-chief, he could not and did not want to believe it.

Near the village of Praca, Rostov was ordered to look for Kutuzov and the sovereign. But here not only were they not there, but there was not a single commander, but there were heterogeneous crowds of frustrated troops.

He urged his already tired horse to get through these crowds as quickly as possible, but the further he moved, the more upset the crowds became. The high road on which he drove out was crowded with carriages, carriages of all kinds, Russian and Austrian soldiers, of all branches of the military, wounded and unwounded. All this hummed and swarmed in a mixed manner to the gloomy sound of flying cannonballs from the French batteries placed on the Pratsen Heights.

- Where is the sovereign? where is Kutuzov? - Rostov asked everyone he could stop, and could not get an answer from anyone.

Finally, grabbing the soldier by the collar, he forced him to answer himself.

- Eh! Brother! Everyone has been there for a long time, they have fled ahead! - the soldier said to Rostov, laughing at something and breaking free.

Leaving this soldier, who was obviously drunk, Rostov stopped the horse of the orderly or the guard of an important person and began to question him. The orderly announced to Rostov that an hour ago the sovereign had been driven at full speed in a carriage along this very road, and that the sovereign was dangerously wounded.

“It can’t be,” said Rostov, “that’s right, someone else.”

“I saw it myself,” said the orderly with a self-confident grin. “It’s time for me to know the sovereign: it seems like how many times I’ve seen something like this in St. Petersburg.” A pale, very pale man sits in a carriage. As soon as the four blacks let loose, my fathers, he thundered past us: it’s time, it seems, to know both the royal horses and Ilya Ivanovich; It seems that the coachman does not ride with anyone else like the Tsar.

Rostov let his horse go and wanted to ride on. A wounded officer walking past turned to him.

-Who do you want? – asked the officer. - Commander-in-Chief? So he was killed by a cannonball, killed in the chest by our regiment.

“Not killed, wounded,” another officer corrected.

- Who? Kutuzov? - asked Rostov.

- Not Kutuzov, but whatever you call him - well, it’s all the same, there aren’t many alive left. Go over there, to that village, all the authorities have gathered there,” said this officer, pointing to the village of Gostieradek, and walked past.

Rostov rode at a pace, not knowing why or to whom he would go now. The Emperor is wounded, the battle is lost. It was impossible not to believe it now. Rostov drove in the direction that was shown to him and in which a tower and a church could be seen in the distance. What was his hurry? What could he now say to the sovereign or Kutuzov, even if they were alive and not wounded?

“Go this way, your honor, and here they will kill you,” the soldier shouted to him. - They'll kill you here!

- ABOUT! what are you saying? said another. -Where will he go? It's closer here.

Rostov thought about it and drove exactly in the direction where he was told that he would be killed.

“Now it doesn’t matter: if the sovereign is wounded, should I really take care of myself?” he thought. He entered the space where most of the people fleeing from Pratsen died. The French had not yet occupied this place, and the Russians, those who were alive or wounded, had long abandoned it. On the field, like heaps of good arable land, lay ten people, fifteen killed and wounded on every tithe of space. The wounded crawled down in twos and threes together, and one could hear their unpleasant, sometimes feigned, as it seemed to Rostov, screams and moans. Rostov started to trot his horse so as not to see all these suffering people, and he became scared. He was afraid not for his life, but for the courage that he needed and which, he knew, would not withstand the sight of these unfortunates.

The French, who stopped shooting at this field strewn with the dead and wounded, because there was no one alive on it, saw the adjutant riding along it, aimed a gun at him and threw several cannonballs. The feeling of these whistling, terrible sounds and the surrounding dead people merged for Rostov into one impression of horror and self-pity. He remembered his mother's last letter. “What would she feel,” he thought, “if she saw me now here, on this field and with guns pointed at me.”

In the village of Gostieradeke there were, although confused, but in greater order, Russian troops marching away from the battlefield. The French cannonballs could no longer reach here, and the sounds of firing seemed distant. Here everyone already clearly saw and said that the battle was lost. Whoever Rostov turned to, no one could tell him where the sovereign was, or where Kutuzov was. Some said that the rumor about the sovereign’s wound was true, others said that it was not, and explained this false rumor that had spread by the fact that, indeed, the pale and frightened Chief Marshal Count Tolstoy galloped back from the battlefield in the sovereign’s carriage, who rode out with others in the emperor’s retinue on the battlefield. One officer told Rostov that beyond the village, to the left, he saw someone from the higher authorities, and Rostov went there, no longer hoping to find anyone, but only to clear his conscience before himself. Having traveled about three miles and having passed the last Russian troops, near a vegetable garden dug in by a ditch, Rostov saw two horsemen standing opposite the ditch. One, with a white plume on his hat, seemed familiar to Rostov for some reason; another, unfamiliar rider, on a beautiful red horse (this horse seemed familiar to Rostov) rode up to the ditch, pushed the horse with his spurs and, releasing the reins, easily jumped over the ditch in the garden. Only the earth crumbled from the embankment from the horse’s hind hooves. Turning his horse sharply, he again jumped back over the ditch and respectfully addressed the rider with the white plume, apparently inviting him to do the same. The horseman, whose figure seemed familiar to Rostov and for some reason involuntarily attracted his attention, made a negative gesture with his head and hand, and by this gesture Rostov instantly recognized his lamented, adored sovereign.

“But it couldn’t be him, alone in the middle of this empty field,” thought Rostov. At this time, Alexander turned his head, and Rostov saw his favorite features so vividly etched in his memory. The Emperor was pale, his cheeks were sunken and his eyes sunken; but there was even more charm and meekness in his features. Rostov was happy, convinced that the rumor about the sovereign’s wound was unfair. He was happy that he saw him. He knew that he could, even had to, directly turn to him and convey what he was ordered to convey from Dolgorukov.

But just as a young man in love trembles and faints, not daring to say what he dreams of at night, and looks around in fear, looking for help or the possibility of delay and escape, when the desired moment has come and he stands alone with her, so Rostov now, having achieved that , what he wanted more than anything in the world, did not know how to approach the sovereign, and he was presented with thousands of reasons why it was inconvenient, indecent and impossible.

"How! I seem to be glad to take advantage of the fact that he is alone and despondent. An unknown face may seem unpleasant and difficult to him at this moment of sadness; Then what can I tell him now, when just looking at him my heart skips a beat and my mouth goes dry?” Not one of those countless speeches that he, addressing the sovereign, composed in his imagination, came to his mind now. Those speeches were mostly held under completely different conditions, they were spoken for the most part at the moment of victories and triumphs and mainly on his deathbed from his wounds, while the sovereign thanked him for his heroic deeds, and he, dying, expressed his love confirmed in fact my.

“Then why should I ask the sovereign about his orders to the right flank, when it is already 4 o’clock in the evening and the battle is lost? No, I definitely shouldn’t approach him. Shouldn't disturb his reverie. It’s better to die a thousand times than to receive a bad look from him, a bad opinion,” Rostov decided and with sadness and despair in his heart he drove away, constantly looking back at the sovereign, who was still standing in the same position of indecisiveness.

While Rostov was making these considerations and sadly driving away from the sovereign, Captain von Toll accidentally drove into the same place and, seeing the sovereign, drove straight up to him, offered him his services and helped him cross the ditch on foot. The Emperor, wanting to rest and feeling unwell, sat down under an apple tree, and Tol stopped next to him. From afar, Rostov saw with envy and remorse how von Tol spoke for a long time and passionately to the sovereign, and how the sovereign, apparently crying, closed his eyes with his hand and shook hands with Tol.

“And I could be in his place?” Rostov thought to himself and, barely holding back tears of regret for the fate of the sovereign, in complete despair he drove on, not knowing where and why he was going now.

His despair was all the greater because he felt that his own weakness was the cause of his grief.

He could... not only could, but he had to drive up to the sovereign. And this was the only opportunity to show the sovereign his devotion. And he didn’t use it... “What have I done?” he thought. And he turned his horse and galloped back to the place where he had seen the emperor; but there was no one behind the ditch anymore. Only carts and carriages were driving. From one furman, Rostov learned that the Kutuzov headquarters was located nearby in the village where the convoys were going. Rostov went after them.

The guard Kutuzov walked ahead of him, leading horses in blankets. Behind the bereytor there was a cart, and behind the cart walked an old servant, in a cap, a short fur coat and with bowed legs.

- Titus, oh Titus! - said the bereitor.

- What? - the old man answered absentmindedly.

- Titus! Go threshing.

- Eh, fool, ugh! – the old man said, spitting angrily. Some time passed in silent movement, and the same joke was repeated again.

At five o'clock in the evening the battle was lost at all points. More than a hundred guns were already in the hands of the French.

Przhebyshevsky and his corps laid down their weapons. Other columns, having lost about half of the people, retreated in frustrated, mixed crowds.

The remnants of the troops of Lanzheron and Dokhturov, mingled, crowded around the ponds on the dams and banks near the village of Augesta.

At 6 o'clock only at the Augesta dam the hot cannonade of the French alone could still be heard, who had built numerous batteries on the descent of the Pratsen Heights and were hitting our retreating troops.

In the rearguard, Dokhturov and others, gathering battalions, fired back at the French cavalry that was pursuing ours. It was starting to get dark. On the narrow dam of Augest, on which for so many years the old miller sat peacefully in a cap with fishing rods, while his grandson, rolling up his shirt sleeves, was sorting out silver quivering fish in a watering can; on this dam, along which for so many years the Moravians drove peacefully on their twin carts loaded with wheat, in shaggy hats and blue jackets and, dusted with flour, with white carts leaving along the same dam - on this narrow dam now between wagons and cannons, under the horses and between the wheels crowded people disfigured by the fear of death, crushing each other, dying, walking over the dying and killing each other only so that, after walking a few steps, to be sure. also killed.

Every ten seconds, pumping up the air, a cannonball splashed or a grenade exploded in the middle of this dense crowd, killing and sprinkling blood on those who stood close. Dolokhov, wounded in the arm, on foot with a dozen soldiers of his company (he was already an officer) and his regimental commander, on horseback, represented the remnants of the entire regiment. Drawn by the crowd, they pressed into the entrance to the dam and, pressed on all sides, stopped because a horse in front fell under a cannon, and the crowd was pulling it out. One cannonball killed someone behind them, the other hit in front and splashed Dolokhov’s blood. The crowd moved desperately, shrank, moved a few steps and stopped again.

Walk these hundred steps, and you will probably be saved; stand for another two minutes, and everyone probably thought he was dead. Dolokhov, standing in the middle of the crowd, rushed to the edge of the dam, knocking down two soldiers, and fled onto the slippery ice that covered the pond.

“Turn,” he shouted, jumping on the ice that was cracking under him, “turn!” - he shouted at the gun. - Holds!...

The ice held it, but it bent and cracked, and it was obvious that not only under a gun or a crowd of people, but under him alone it would collapse. They looked at him and huddled close to the shore, not daring to step on the ice yet. The regiment commander, standing on horseback at the entrance, raised his hand and opened his mouth, addressing Dolokhov. Suddenly one of the cannonballs whistled so low over the crowd that everyone bent down. Something splashed into the wet water, and the general and his horse fell into a pool of blood. No one looked at the general, no one thought to raise him.

- Let's go on the ice! walked on the ice! Let's go! gate! can't you hear! Let's go! - suddenly, after the cannonball hit the general, countless voices were heard, not knowing what or why they were shouting.

One of the rear guns, which was entering the dam, turned onto the ice. Crowds of soldiers from the dam began to run to the frozen pond. The ice cracked under one of the leading soldiers and one foot went into the water; he wanted to recover and fell waist-deep.

- Cherginets Boris Nikolaevich History of formation and combat path

- Hitler's field marshals and their battles I was Hitler's adjutant Nikolaus Belov

- Code of Honor of a Russian Officer in the Tsarist Army

- Biography of Pavel Dybenko Pavel Dybenko, the fate of the main sailor of the revolution

- The connection of the first and second Western armies in Smolensk In 1812, the Western army was commanded by

- As soon as one gets dirty, it becomes weak and is eaten

- Nuremberg trials Nuremberg trials protocols of interrogation of the main war criminals

- Constant change in the value of the same values

- Reflection of turnover in the accounting model How to find the movement of goods in 1C

- reasons and stages of transition from batch accounting system

- Deductions from employee salaries in 1C

- History of the emergence and development of the Uzbek language

- Call a plumber Miass

- Concept of programming paradigm Declarative and procedural memory

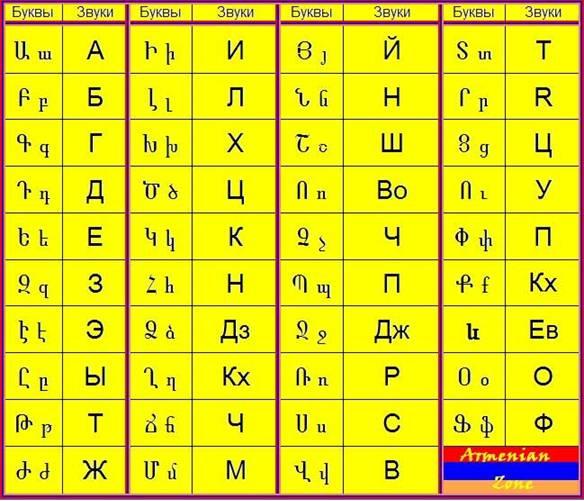

- Armenian alphabet with English transcription

- Hephaestus - lord of fire and metal

- Large-scale confirmation of the “African” theory of human origins has been obtained

- Under the wolf sun What language group do the gypsies belong to?

- Essays for schoolchildren Tvardovsky it’s no fault of mine

- The first chairman of the Tunguska volost